Posts Tagged ‘crime prevention’

Posted on: April 17th, 2014 by Smart on Crime

We all agree that both the direct and indirect victims of crime deserve society’s help and support. Victims want services to help them come to terms with their trauma, loss, and grief so they can move on. Government supported services, compensation for their injuries, and measures to prevent both the occurrence and reoccurrence of crime are important to victims of illegal action. Recently, the Victims Bill of Rights has proposed to provide this support not by establishing government programs for victims’ assistance but instead by giving victims legal rights and a role at the heart of the justice system. But this role for victims represents a departure from the principles of criminal justice embedded in our legal tradition and protected by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Progress in the development of criminal law was marked by an evolution away from private disputes between victims and alleged wrongdoers and toward the administration of justice by the state. As mentioned in October 27, 2013 opinion piece in the Star:

“one of the greatest innovations of the criminal justice system was the realization that the wrongful injuries people inflict are primarily offences against the public moral order represented by the Queen, not just particular harms to individuals in a given situation.”

While individuals could sue in civil cases to recover for losses resulting from wrongdoing, it was the state that ensured that punishments for wrongdoing responded to criminal harm as an injury to the values of a stable, secure society. In this role, the duty of the state was to punish the criminal harm to the victim while still respecting the basic humanity of the criminal. This second branch of the state’s duty secured the rights to fair trial and appropriate punishment on conviction for the accused, which are the hallmark of the just society. The era of the blood feud and the personal vendetta was over.

The extent to which the present Victims Bill’s ‘rights’ will in fact put victims at the heart of the criminal justice system may be illusory. Bill C-32 is clear that the only parties in the criminal justice system will continue to be the accused and the Queen. The Bill also provides that the rights of victims will be applied in a reasonable manner so as not to disrupt the “proper administration of justice” by causing delay or interfering with the discretion of the criminal justice system decision makers. Victims are expressly not made parties, interveners, or even observers in any criminal justice proceedings. No right to seek a judicial remedy, no claim for damages, and no appeal arises if victims’ rights are infringed. Expectations by victims about their entitlements from the justice and corrections system may well exceed what already over-burdened justice and correction officials are able to provide and victims may well feel disappointed by their newly acquired rights. The only remedy provided in the Bill for that disappointment is the capacity to file a complaint. In view of all these limitations, victims may well come to question whether they received a Bill of Rights or a Bill of Goods.

Definition of Victim

‘Victim’ is defined broadly in the Bill as an “individual who has suffered physical or emotional harm, property damage or economic loss as a result of the commission or alleged commission of an offence”. The offender is expressly excluded but his or her family members who may have incurred harm or damage as a result of the crime are not. If the victim is deceased or incapacitated, the Bill specifies the next of kin or care provider who may exercise the victim’s rights. While the definition of victims refers to ‘individuals’, ‘communities’ are also authorized to make victim impact statements. It is unclear what collection of interests will constitute a ‘community’ and whether community victim impact statements will be considered at all stages of the criminal justice process or just at sentencing.

Rights for Victims

Bill C-32 includes four categories of rights for victims relating to information, protection, participation, and restitution. Generally, providing information about the criminal justice and corrections system and ensuring adequate protection for victims in the criminal justice system is desirable as long as they do not infringe the accused’s ability to make full answer and defense or privacy rights. Since it is the proposed rights to participation and to restitution that pose the most significant challenges to maintaining a fair and effective justice and corrections system, we will concentrate on those.

The victim’s participation rights include the right to convey and have considered his or her views about decisions to be made relating to the investigation, prosecution, and adjudication of the alleged offence and also regarding the corrections and conditional release process. As written, this appears to include the right to provide victim impact statements at each stage which will have to be taken into account.

Unavoidably, these new procedures will cause delays. Despite falling crime rates, the criminal justice system is already overburdened and slow. Long waiting times are not only difficult for those awaiting trial, particularly if they are in detained in remand facilities, but they can violate rights to a speedy trial resulting in an inability to bring an accused to justice. Decision makers in the justice system try to move cases toward resolution as efficiently and fairly as possible. Not only will these decision makers be required to provide information to victims who request it, but they will now be asked to consider the views of the victims about the decisions they are required to make. The decision maker will also be compelled to receive and consider a victim impact statement. While this would take time even if there were only one victim, it would become quickly unmanageable with complex cases involving multiple victims, such as a sophisticated fraud or terrorist incidents. If the stated participation rights of victims lead to costly delays or result in prosecutions having to be dropped due to violations of the Charter right to a speedy trial, is justice served?

Further, victims’ participation rights could conflict with justice officials’ obligations to make impartial decisions when exercising their discretion. For example, a prosecutor may decide whether to proceed to trial with charges based on the public interest and the likelihood of a conviction. A victim impact statement reflecting the trauma experienced by the individual may not be relevant to the determination facing the prosecutor yet he or she would be required to consider it. It is not in the public interest to proceed to trial if there is no chance of a conviction despite a prosecutor’s sympathy for the plight of the victim.

Bill C-32 provides that every victim has the right to have the court consider making a restitution order against the offender and have it enforced as a civil court judgment. The introduction of a right to have monetary order for the victims considered by the court skews both the principles and practices of the criminal justice system. As already discussed, most modern criminal justice systems have evolved away from a system of monetary penalties paid by the criminal or the criminal’s family to the victim. Some countries still have criminal justice systems that include ‘blood money’ — a pay out to victims in satisfaction of a crime. With the proposed Victims Bill of Rights, this outdated practice could be revived in Canada.

While empowering judges to consider ‘restitution’ and even ‘compensation’ is not new, these concepts have been embedded in criminal justice principles. ‘Restitution’ historically had been based on principles of precluding unjust enrichment and benefitting from one’s crime. If a person had stolen property or had sold it, the court could order the property or proceeds of the sale be returned. Over time, the understanding of ‘restitution’ changed to include damages for harm caused to the victims. Orders for restitution or compensation became sentencing options for the judge to consider in assessing the totality of the punishment. In this way, the monetary award is limited by what was a fair and proportionate penalty for the offence. If the offender paid a monetary award, this would discharge some of all of his or her punishment for the crime. Nothing precluded the victim from seeking further damages through a civil court process.

Fines and other punishments involving monetary payment by the offender raise some profound fairness issues in the criminal justice system. Simply put, it is much less onerous for a wealthy person to pay a fine than a poor one. Unless something like a day-fine system is adopted where the fine is based on percentage of income, then this type of sentence violates the equality of punishment essential to a fair criminal justice system. Accordingly, judges have imposed fines, surcharges, restitution and compensation orders with restraint.

While normally judges are required to assure themselves that the offender is capable of paying a fine before imposing it, the Victims Bill of Rights specifically provides that the offender’s financial means or ability to pay does not prevent the court from ordering restitution. Far too many accused are poor, marginalized, battling mental health and addictions and without the lawful means to provide financial compensation to others. If a judge does not impose restitution as part of the sentence, he or she will have to explain why. Judges will likely feel more pressure to make these awards.

The preference for restitution orders also builds an undesirable incentive into the system. With the possibility of having damages covered by just filing a form with the courts, how many more people will identify themselves as victims? How many victims will forego the possibility of an easy recovery of losses to participate in restorative justice practices or other measures that might resolve the issue outside of the formal justice system?

The rights to restitution run the risk of inappropriately importing civil justice concepts into the criminal justice system and undermining core principles of fairness.

Conclusion

The Victims Bill of Rights creates a tension: If the victims’ rights as set out in the Bill are applied, they threaten to undermine principles of criminal justice by placing victims at the heart of the criminal justice. This would erode core principles by slowing down an already overburdened system and skewing it toward a tool for personal vengeance and away from objectivity. If the victims’ rights as set out in the Bill are not applied, then victims will be disappointed and their confidence in the criminal justice system will be further reduced. And there is every reason to believe that the promised rights for victims will fall short of expectations. The Bill provides victims with no standing in the proceedings, a complaint mechanism as a remedy for breached rights, and requires that the Bill be interpreted reasonably so as not to delay proceedings or interfere with the discretion of justice system officials. Rather than create a tension between justice principles and victims’ rights that will be felt by victims and justice and corrections officials at every stage of the system, it would have been better to focus on rights to victims’ services, state-guaranteed compensation, and victim prevention measures. These would have addressed some of the real needs of victims without creating likely harmful pressures and unrealistic expectations of the criminal justice system.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

In 2011, she became the Executive Director of the John Howard Society of Canada, a charity committed to just, effective, and humane responses to crime. Ms. Latimer has a law degree from Queen’s University and a M.Phil. from the University of Cambridge.

She is also a part-time professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa. Her interests are in criminal justice, youth justice, corrections laws, human rights, justice systems programs and policies, and policy and law reform.

Reprinted with permission from the author.

Posted on: April 10th, 2014 by Smart on Crime

My path in crime prevention started almost 20 years ago; my formal path that is. But, even prior to that, my work with those who were marginalized and/or victimized was also “crime prevention”. I just didn’t know it then. I certainly didn’t call it that. I know better now!

Justice goes well beyond the walls of courthouses and prisons to the heart of citizen capacity and imagination. In a way, justice lives in a tension between security and democracy. Security, of course, frequently uses methods to exclude certain people from certain places. Democracy, on the other hand, can be measured by the extent of our willingness and ability to include all people. Places where everybody matters, even those, or maybe especially those, who make us somewhat uncomfortable, are something to aspire to in democracy. But measures of security will often tell us the opposite. Herein lies the rub. And it is often no more obvious than in our interventions with youth.

Throughout time youth have caused us some discomfort. Not because of whom they are, but because of the associations that have been created between youth and crime. How we treat those who are in that critical transition between childhood and adulthood is an essential measure of the character of our community. How we interact with youth, how we express ourselves to and about them, says so much about us. It may not actually have a whole lot to say about them.

“We must learn to work for young people but also with young people. Our society must learn to trust them and avoid generalizations which stigmatise them, or portray them as potential criminals. The challenge to us all is to guarantee the legitimate right to safety of each and every person without discrimination and the scapegoating of youth.” (European Forum on Urban Safety, 2000).

It is good news then that progress often seeds itself in grounds of dissonance. Discomfort can be an opportunity for growth and learning if we only allow it to be.

inREACH was a golden opportunity. It brought discomfort in so many ways that we can only be grateful. We got to test assumptions about youth generally and street gang prevention specifically. We ended up rocking our boat of easy answers.

I am no expert in crime prevention. I have searched high and low for such person and have yet to find one. I am certainly not it. There are no bumper stickers in crime prevention no matter who brings them to you (and sometimes those who bring them have formidable power). The issues of crime, youth crime and street gang related crimes are immensely complex. They defy convenient truth. Sure, it is true that there is solid evidence to suggest that some children and youth are a greater risk of coming in conflict with the law. There is also solid evidence to suggest that this can be prevented. It would therefore make a whole lot of sense that we invest more in preventing children and youth from becoming involved in crime than we do in warehousing them through their teenage and adult years. But such sustained commitment to community safety can only thrive in an environment that distinguishes facts from fiction. And few things seem to be as fraught with myth and fiction as youth crime.

And that was the whole point. inREACH was about learning what works not what we believe to work. And whenever we are on a learning path we will encounter screaming successes as much as fabulous failures. At inREACH we had to not only dispel the overused myth that connects youth and crime, we also had to dispel the myth of singular professional expertise, as well as the myth of being a community where inclusion and collaboration are always easy. We finally had to learn that outcome measures are an empty promise at the beginning of such journey.

What a gift!

And without the voices of youth and true efforts at inclusion that gift would not have been possible.

But “kids at risk” are not supposed to be engaged in shaping public policy; they are supposed to live at the fringes of the community – not on its stages. But we found that listening is a most powerful method for changing trajectories. Listening can begin to untangle the complex interplay of individual traits, family, community, and wider social supports. And when we listen we learn so much.

- We learned that risk factors do not follow a neat mathematical “1+1 = 2” formula. As much as one more risk can bring a person to the precipice of crime, so one resilience factor can stop him or her from falling off. This resiliency can be sparked by a significant adult who refuses to give up, a teacher with an eye not only to the irritating behavior but the roots of it, a school that deals with the social inclusion first and academics next, programs which assist stressed families by first and foremost meeting their essential needs of life.

- We also learned that we can ALL be essential partners in this quest for safer communities and civic vitality if we make the connection between basic needs (such as food and shelter) and meaningful engagement, sense of belonging and viewing others as opportunities not threats.

- We also learned that knee-jerk reactions, approaches rooted in fear, or a philosophy of blame are the greatest barrier to successful prevention.

In the never ending circle of seeking who is to blame we have become confused and numb to our own opportunities to be part of scripting a whole new story about us and the young people among us – ALL young people. In a way, inREACH was an opportunity to test our resolve to focus on prevention sometimes despite of it all. It was our opportunity to wiggle in discomfort as we sought out momentums for sustainable change.

The moral of the inREACH story is that no one system alone is equipped to deal with the complexity of gang related crime. We had to work in partnership. It was not a choice. Hats off to Dr. Spergel for saying all that so many years ago, long before we ever even conceived of inREACH. But “partnership” is not an old boys/girls club or tired relationship on auto pilot. Partnership is a vital agreements to work together, to share a vision, to establish a set of values, to be held collectively accountable, to disagree, and disagree some more, but to never stop moving forward together. Partnership does not end at the board room doors but rather moves us into the heart of the service we provide. That was the task we set for ourselves and it was a difficult task indeed.

The confession that easy answers are little else than a distraction from the larger social and community roots goes hand in hand with the invitations to citizens to overcome such psychology of learned helplessness. Learned helplessness is the outcome of a gradual but persistent chipping away at our collective confidence that anything can be changed let alone that we can be part of that change agenda.

Ask most people what to do about crime and at first they reach for the 911 dial. Give them the opportunity to recognize the power of everyday action and they can rally together in a way that goes beyond our wildest imaginings. The neighbourhood mobilization work of inREACH exemplified that more than anything I have ever seen. From parents to teachers to artists; when we merged the stories of those in social services with the stories of everyday citizens and those with lived experience, a comprehensive plot emerged in which truly everybody mattered.

Too often have we developed services first and the asked why. In this “we know what is best for you” mentality we often even maintain programs out of tradition, not because they worked. Such skewed problem solving is, at least in part, the outcome of organizational distance to the people we serve. inREACH youth came up very close and personal. And we were and are richer for it.

Some answers of convenience are not wrong in and off themselves. They are just wrong by way of their omissions. inREACH youth had a voice and in hearing that voice we designed an approach that was rooted in their reality even if it wasn’t always popular or comfortable. In helping them to break their silence we had to face our own fear of contempt, censure, judgement or lack of recognition. But in the words of Audre Lorde: “The fact that we are here is an attempt to break the silence and bridge some of the difference between us, for it is not differences which immobilize us but silence”.

I so look forward to tomorrow. Tomorrow is our chance, free of the confines of funding (yes there is freedom in not being funded) to again amplify the voices of those who live and lived it, and those who had the courage and wisdom to live it with them.

In the end, it is up to all of us to say: OK! We hear you! Now what?

Author: Christiane Sadeler is the Executive Director of the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council.

Posted on: April 7th, 2014 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

Before inREACH ended in December 2013, I shared 5 important lessons learned from the inREACH gang prevention project with the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council. While project funding has ended, some parts continue and there is much to be learned about addressing youth gang involvement in our community for the future. Here are some highlights.

1. What are your assumptions and values?

We need to ask ourselves this central question – what are the fundamental assumptions and beliefs we have about the young people we work with? Do we feel people are broken and need to be fixed? Or – do we believe people are full of capacities and if supported correctly, they can realize their potential? I’m not saying people don’t come with their problems, but the question is what are we focused on because that informs how you do the work. It took us a while to get this right. This idea was expressed well by a youth participant:

“It’s…for us, run by us and gonna involve all of us..What do you want to see in your community, and what are your personal talents or anything that is special to you that you want to show everybody else, and maybe those people might like it too right? So- opening new opportunities. It’s not just to keep kids off drugs but for under-privileged kids, kids who may have never had a chance to be part of something like you know…discover their love of art…so it’s giving everybody a chance to actually do…the things they want to do, so that’s why I started coming.”

This is powerful because it’s raising the bar. It’s not just getting youth out of the gang – but getting them into a job or back in school and even realizing some of their hopes and dreams. If you believe that people are full of possibilities – then the work is geared more to helping people realize that potential versus simply preventing them from doing something.

2. Gang Prevention Is:

- addressing underlying issues

- not about getting a kid to take off the bandana

We often heard – “we’ve got this kid, he’s in a gang – fix him.” So often in our case management and system navigation work, it wasn’t about getting this young person to take off his bandana or to stop hustling or whatever, we never approached the work in that fashion. But it was about the underlying issues and working on them. Mostly we were dealing with issues of poverty, untreated trauma, family breakdown, substance abuse, disengagement and lack of opportunities. These are the problems that young people and gang members and people in general are dealing with. We want to demystify that label of gang member that says their needs are different than any other groups. These same issues are the drivers behind the behaviours.

3. Gang prevention is:

- increasing engagement and inclusion

- working at individual and community levels

Young people demonstrated so clearly that they WILL engage. This matters because pro-social relationships and connections are essential for preventing youth from participating in gangs.

Unfortunately, adolescents and young adults are much less involved in community activities than other groups, particularly those experiencing marginalization due to where they live or challenges they face. Researcher Mark Totten says “there is an epidemic of social exclusion in Canada.” inREACH very successfully supported young people’s inclusion and engagement, in community centres, recreation, school, employment, services and more. This is a promising way to build assets and address risk factors in a holistic and non-stigmatizing way. However, it wasn’t just about engaging individual youth. The community was also mobilized and systems needed to make some changes in order to be more inclusive.

4. inReach is an example of an effective hub model

inReach is a comprehensive wraparound hub model demonstrating an effective way to support young people. It was comprehensive because all the right supports, services, staff and organizations were involved. It was a mobile hub which was key for meeting young people where they’re at – whether at the office, Tim Horton’s or their home. Dedicated multi-disciplinary teams brought diverse skills to the work and learned strategies and skills from each other. It was not done at a desk.

5. You Need The Right People On The Bus

You need to have the right people and organizations involved in the project and that was really key to the success of inREACH. People have to be there for the right reasons, share the same vision and be able to check their egos at the door. It can’t just be about what’s good for your own organization. Collaboration requires a thoughtful discussion before you bring people on the team. Everyone involved with inREACH was fully invested and went above and beyond because they were passionate and believed in it.

The community should be proud of all that it has accomplished.

Co-authors: Dianne Heise & Rohan Thompson – Dianne Heise is the Coordinator of Community Development and Research with the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council and worked with the inREACH project while she was a Master of Community Psychology student at Wilrid Laurier University. Dianne also worked on the final evaluation of the inREACH project with Dr. Mark Pancer (WLU).

Rohan Thompson was the Project Manager for the inREACH Street Gang Prevention Project (2010 – 2013). At the end of the project, Rohan returned to his role with the City of Kitchener.

Rohan Thompson (L) and Dianne Heise (R)

Posted on: April 3rd, 2014 by Smart on Crime

Alison Neighbourhood Community Centre is neighbourhood-based organization that works with volunteers to support residents who live in the Alison Neighbourhood in East Galt, Cambridge. We support residents, families, children & youth by offering after school programs, youth drop-in programs, community events, family outreach services, and volunteer opportunities.

As a member of the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council and as community partners of a couple of the InReach project host sites, we were able to hear about some of the wonderful opportunities to which the youth were exposed as a result of InReach that they would not have experienced otherwise.

How InReach Resonated with the Work We Do

- We too, focus on building on strengths and capacities of young people

We have worked with youth who have great dreams and aspirations for the future, but have trouble putting their vision into a workable plan. On the other side of the coin, we have worked with youth who have little to no confidence in their abilities, thus requiring a little more encouragement and a little more trial and error in determining what really gets them motivated and excited.

In our experiences, many youth have difficulty simply picking up a new hobby as a means to divert themselves from more harmful and negative activities. Let’s say a young person decides to try something new: Inspired by an Instagram pic of a friend of a friend’s cousin rock climbing out West, Andrew decides he wants to give it a try. A few initial barriers come to mind: Other than that distant personal connection, he doesn’t know anyone else who rock climbs, he doesn’t know where he would go to rock climb, and has no idea what is needed to get started. How much is it to join? Do you need a membership? What type of equipment is needed? Does that cost more money? The idea is now overwhelming. For a youth who has not had many life experiences nor opportunities, it is likely that these questions wouldn’t even be on their radar. It is much easier to continue along their existing path, wherever it may lead.

In our experience, the recipe for youth engagement is as follows:

- Exposure to a new activity must take place in an accessible space where youth feel safe, where they won’t feel like they are being judged and feel comfortable to try, fail, and then try again

- In order for this to happen, relationships must be built with program staff. And in order for this to happen, staff must be skilled in outreach and community development practices so that they can effectively meet the youth where they are at before they will even walk through your door

- Youth need to be involved in the planning process and have input and control over what happens next

- It takes time, commitment to seeing the initiative through, trial and error, one-to-one support, and constant encouragement to ensure that youth are getting the most out of the program.

Bottom Line: You cannot expect certain youth to simply sign up for an activity, attend regularly, and thrive without support, a trusting relationship and input into the program’s design and execution.

- We have learned to adapt to the growing complexity of the needs and issues of youth

We offer programming for youth under the guise of recreation. When I first started working in the field, I had a very pretty picture in my mind about what the harmonious world of recreation should look like: Mom or Dad would drop off their kid for our program, (on time), sign-in would be completed in an orderly and organized fashion, and we would all participate in an rousing round of basketball. At programs end, the youth would depart safely for the evening and everyone would be so happy. I hope you can smell the sarcasm here, because this picture couldn’t be any further from our reality. On paper, we offer programs such as Teen Night, Basketball, Girls Night, etc. In reality, we offer mentorship, leadership development opportunities, a place to belong and be heard, support and guidance, a respite from family and relationship trauma, something to eat, relief from the stresses of coping with depression and anxiety, an escape from the pain and constant disappointment of poverty, an opportunity to practice speaking English, access to individualized supports such as counselling, emergency food sources, career resources, addictions supports, relationship and grief therapies, and the list goes on and on. Ultimately, by the time we have a chance to check in and talk to everyone who was fortunate enough to even arrive to the program, there often isn’t time to play basketball.

- We need help keeping programs like these going so that we can reach more youth

Just because the InReach project is now “complete” doesn’t mean that there still isn’t more work to do. With as many partners, staff, support agencies and youth impacted by InReach, I hope that the trajectory of this valuable project will not be lost and its lessons forgotten. The truth is, there are thousands of youth living in the Waterloo Region that could really benefit from a community treatment team; a one-stop-shop where youth can access support to face a combination of issues (see above) unique to only them, right in their own neighbourhoods. Effectively addressing these issues takes partnerships, patience, commitment, resources- all things that that the InReach project so successfully exemplified.

Author: Courtney Didier is the Executive Director of Alison Neighbourhood Community Centre in Cambridge. She is very passionate about creating sense of community and inclusion, not only in her neighbourhood, but across the Waterloo Region. Courtney is expecting her first child any day now!

Posted on: April 2nd, 2014 by Smart on Crime

Being an avid hockey fan, I await the joys of the upcoming Stanley Cup playoff run. But with this expect many interviews, with standardized questions with the same responses from each player. The questions never change based on a given answer, and the answers never change from game to game, and year to year for that matter. They are all cliché based interviews. How is this relevant to inREACH?

Having been with inREACH, it became quite evident, that the youth we worked with often experienced clichés in their lives. They were labelled, stereotyped, and their behaviours were often predicted by the adult world around them, yet most of the time no one knew anything about them. Outside of where they lived, or who they hung out with, or the school they went to, or perhaps what they look like, do many even know these youth? The label which is the umbrella they live under is their cliché.

While working with inREACH, the approach we used broke down these barriers, the labels, the assumptions. That is what worked. Did we listen to them? No; we heard them. We can use our own clichés about giving hope, opportunity, a chance, but it only works if we know what to give. That was done by hearing their story. Their story does not have to be a given. It is not just about where they have come from, and what they are going through, it is also about where they want to go. If we hear them, we can help them. inREACH worked because no assumptions were made. Each youth had their own “Stanley Cup” they wanted to lift, but the battle to get there was the unknown. After each session or meeting with a youth, there were no cliché answers or questions. There was the concept of acknowledgement of ability, an identification of assets, and no reason to suggest why that youth could not raise that cup, whatever that cup was from him or her.

There was a time where we were asked to do a presentation on working with high risk youth on behalf of a community agency, and the reason for such information was the staff was stressed due to not feeling successful in working with this population. Initial feedback as to why the training was needed was the youth do not listen; they are always angry, disrespectful etc. Perhaps part of the issue is as adults, we make assumptions of where these youth have come from. This was a huge learning curve I believe many of us have yet to master.

Recently I watched the film “Short Term 12”, about youth in a group home, and a new staff member in the film was asked to say a few words to introduce himself to the group. His response was: “I always wanted to work with under privileged youth”. That comment didn’t go over very well. My first reaction was shock really, as the moment the categorization of ‘under privileged’ was used, any potential trust is already gone (as the youth were not too happy). The scene reminds me so much of what inREACH was about. Youth are…really….just youth. No adjective required. And really, I do think that is what is being missed. That point was driven home while with inREACH.

Often, we as adults rely on labels, as they are easy to work with clichés that fit into a nice little box for the ease of comfort.

In my continued work, I think it is of the upmost importance to truly find out what the youth needs, or wants, and feels. To reflect on what the youths’ words are, shows they have been respected, and valued, and heard. That is the start of their quest for their Stanley Cup.

Moving forward, what is my message? I won’t give any clichés here that you will assume I should be making now. What I will say, is do you know the path I took as a youth to get to where I am right now (working in social services for 14 years)? I will bet most likely not. I was a youth. We all were. That is the cliché I will end off on!

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at John Howard Society with the Youth in Transition Program, a program for Crown Wards. And want to know a fun fact…? I still play my major passion every week…HOCKEY!

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at John Howard Society with the Youth in Transition Program, a program for Crown Wards. And want to know a fun fact…? I still play my major passion every week…HOCKEY!

Posted on: April 1st, 2014 by Smart on Crime

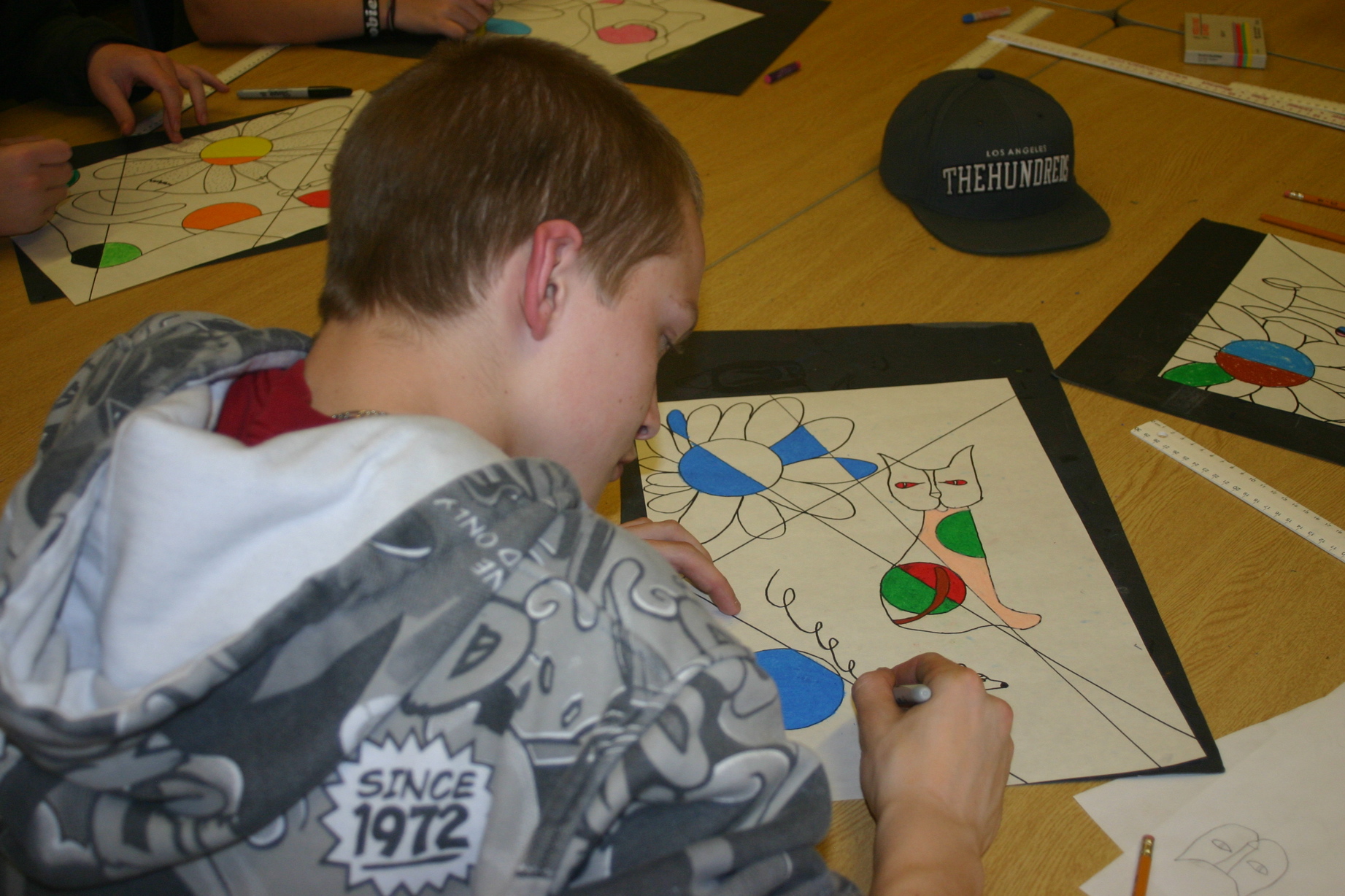

I spent a couple years working as a Youth Outreach Worker with inREACH. I spent most of my time in the Preston Heights neighborhood and also in the Paulander community. I was part of the Community Mobilization phase of this pilot project and assisted the youth in running events/programs.(ie.. Art Studio, weekly youth drop-in, sports evenings, homework help group,..) Our approach with youth was very relational and strength-based. inREACH provided an environment that definitely steered us away from the traditional way of working with youth.

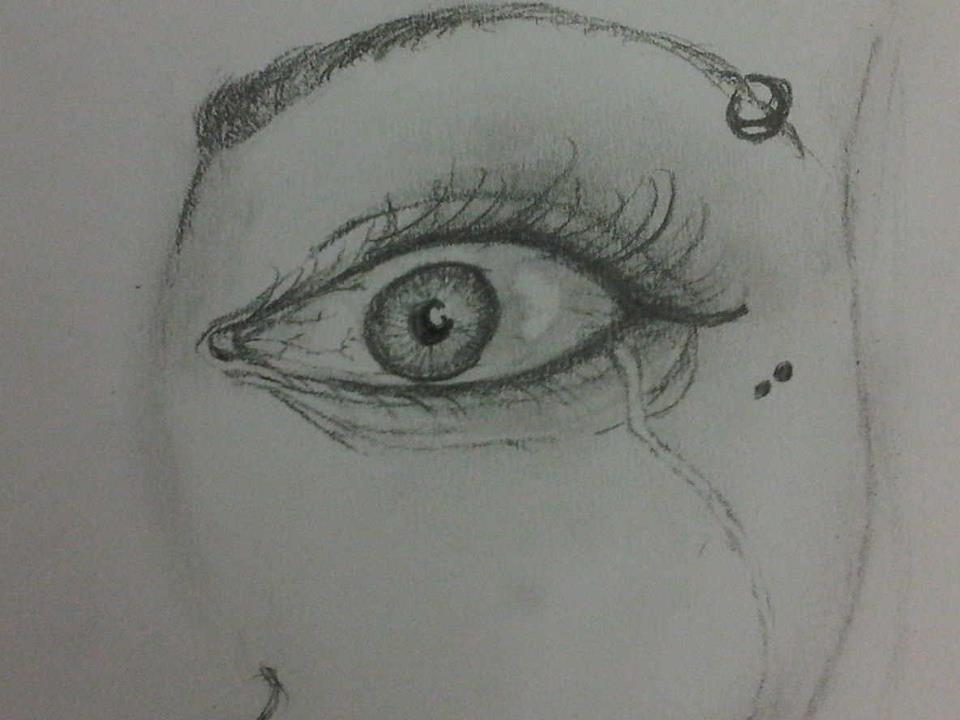

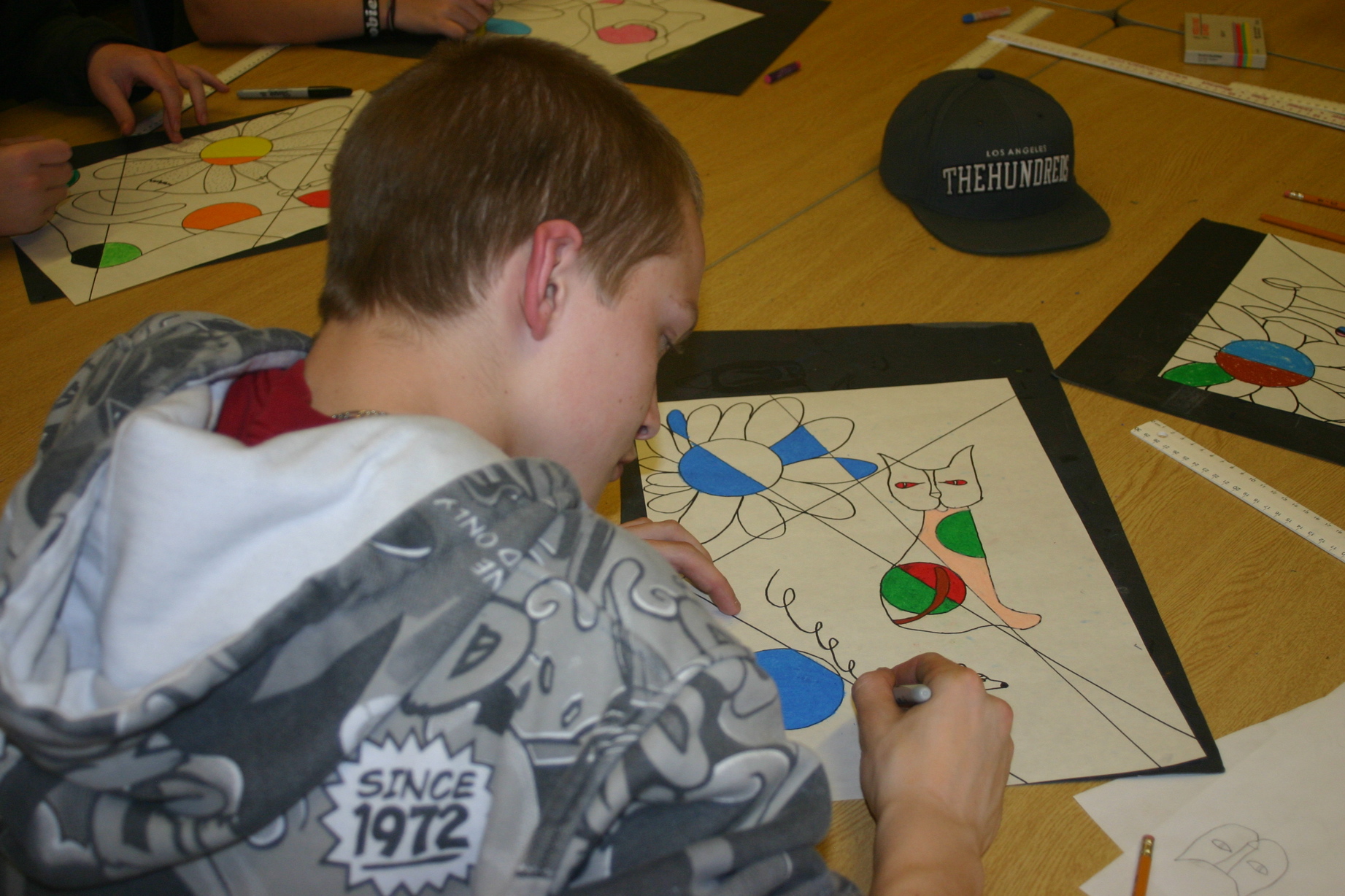

A big part of these two years was assisting the youth in opening a Youth Art Studio. This studio gave opportunities for at-risk youth to express themselves through the creative arts. It gave the youth a chance to engage in a new and healthy outlet to express their emotions, as well as cope with current and past adversities. I also assisted these youth in running their very first Art Show at a local gallery. Some sold their art, some made the paper; but more importantly I noticed a huge boost of confidence in each of the youth who took part in this.

A big part of these two years was assisting the youth in opening a Youth Art Studio. This studio gave opportunities for at-risk youth to express themselves through the creative arts. It gave the youth a chance to engage in a new and healthy outlet to express their emotions, as well as cope with current and past adversities. I also assisted these youth in running their very first Art Show at a local gallery. Some sold their art, some made the paper; but more importantly I noticed a huge boost of confidence in each of the youth who took part in this.

Over the years I always found the act of creating art a very therapeutic experience for the youth I worked with.

With inREACH closing due to lack of sustainable funding, I decided to start a for-profit business that would fund an Art’s program for at-risk youth. I started Art Innovators Waterloo Region. I hired a team of Art Instructors in the beginning of 2013, and we now provide after school/lunch time Art Programs in over 30 schools within 7 local School Boards. These programs are all parent paid. We also now run Art Camps, Corporate Team building Art Classes and Seniors Art programs. I use the profits from these programs to fund art programs for at-risk and disadvantaged youth.

I run programs in local alternative schools and youth shelters like Argus (males), Argus (females), Monica Ainslie Place, New Dawn, New Way, etc. I am even able to continue to connect with some of the youth I had worked with through the inREACH project. I am very excited to be running an art program with Community Justice Initiatives in a local Custody facility (GVI). I am also able to offer free scholarships to many families who cannot afford our Art Program in each of the schools we partner with. One of my free art programs starts next week in a Waterloo Region Catholic school in the Paulander Neighborhood.

I feel that my experience with inREACH had an important part to play in starting Art Innovators here in the Waterloo Region.

Author: Paul Field

Author: Paul Field

I am the middle child of 7 brothers and grew up in the country. I spent the last dozen years working in the Social Work Field in settings such as Schools, Group Homes, Rehabs and Youth Drop-in Centers. My passions have always been working with youth, travelling and creating Art. I am blessed with my beautiful wife Liana and two amazing children; Willow and Lachlan!

Posted on: March 31st, 2014 by Smart on Crime

My experience with the inREACH project began when the Community Mobilization team was formed. I was one of 4 Youth Outreach Workers, working primarily in the Courtland Shelley community as well as in the Paulander neighborhood, both in Kitchener. Our job as Youth Outreach Workers was to work within the neighbourhood to help make young people feel a greater sense of belonging and security within their community.

inREACH fostered a working environment that not only allowed us, but encouraged us to work outside of the box. I’d be lying to say the task was not daunting at first. In my previous experience working as a Youth Worker I had never been given such flexibility and confidence within a position to achieve the desired outcome; an outcome that was not based on the amount of programs ran or number of program participants but the ability to engage youth in their community. We were not given a method to do this; it was easy to see that each of the communities we worked in were uniquely their own. We were introduced to the Spergel Model to use as a foundation and approached our communities in a very strength based, relational approach.

What I appreciated most about working with inREACH, and what I have made a conscious effort to take with me in my work is the time we were given to establish relationships. I spent the first couple months getting to know and understand the community I was working in. I was given the flexibility to do this in many different ways. I spent time outside playing with the kids, going to adult classes or food distributions at the community centre, attending parent council meetings, sharing food with youth, and just hanging out in parks, the malls and parking lots. Any place I thought I might connect to the community I went. inREACH and my working agency, House of Friendship gave me the time to make my visual presence in the community known, and to establish trust and rapport with the youth and their families. Although there were days this time spent within the community did not seem valuable, it was undoubtedly critical to the success of working with the youth in these communities – taking the time to establish a solid relationship allowed for programs, education and training to be successful later in the project.

Through my experience at inREACH I also saw success in an alternative approach to programming. Many community agencies believe that after a certain age youth are not interested in being involved in their community or attending programming at a community centre. I myself have even been guilty of some of those thoughts, however after running strong programs I realize now that it is all in the approach. Creating successful, well attended programs began with the relationship that was formed between the youth and me in the first couple months of working in the community. Through this relationship I was able to discuss with the youth what types of programs they would like. Focusing on their strengths and interest, the youth were involved in the planning and implementation of the programming, right down to the days and times they thought would work best. This created a program that they had interest and ownership in. I also learned to allow the programs to change and be flexible. Programs that initially were successful became less attended and needed to change according to the youth and their needs. Our funding from inREACH allowed us to do many impactful things with the youth outside of their community. Although these things were very important I saw how programming within their community helped the youth to feel a sense of belonging and safety within their neighborhood.

I am pleased to say that the Courtland Shelley Community Centre continues to run youth programs established through inREACH. I have been fortunate enough to remain working at these programs and to sustain relationships with many of the youth I worked with through the project. House of Friendship allows me to continue using approaches that help to enhance my relationship with the youth and run programs that represent their changing needs and wants.

My experience with inREACH has been invaluable. Working with the project has strengthened my skills and competency as a youth worker. I am proud to have been a part of such a unique project that united so many community agencies in collaboration. The inREACH project may have ended, but I take with me inspiration from the youth as well as for the future of youth engagement in the Waterloo Region.

Author: Krista McCann

Author: Krista McCann

With an education in Child and Youth Counselling Krista McCann has spent several years working with marginalized children, youth and their families. Krista is dedicated to creating relationships and environments for youth to thrive.

Posted on: March 27th, 2014 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

I agree with the sayings – ‘there’s always more to learn’ and ‘it’s never too late to learn.’

I lived this out when I returned to university for a Masters degree the same year my daughter started university. Luckily she wasn’t too embarrassed to be at school with her mom. My timing turned out to be perfect for another reason as well. During my time in school I had the amazing opportunity to be involved with the research and evaluation of the innovative and highly successful gang prevention project, inREACH. I can guarantee you; I learned something new every day.

An excellent summary of the evaluation report for inREACH highlights a LOT of really important learning and accomplishments as a result of this collective community effort over the past few years. Sharing our story: Lessons learned from the inREACH experience describes how the project was implemented, the young people it served in the treatment and prevention programs, and the many positive impacts of the project on young people, neighbourhoods, organizations and the community as a whole.

The most important lessons and understandings learned from inREACH will inspire community action toward a future where all young people feel part of a caring community and have the opportunities and the supports they need and deserve. But, any evaluation isn’t even worth the paper it’s printed on if it just sits on a shelf. We need to apply the evaluation findings so that we can affirm what might already work but also make changes where needed.

The most important lessons and understandings learned from inREACH will inspire community action toward a future where all young people feel part of a caring community and have the opportunities and the supports they need and deserve. But, any evaluation isn’t even worth the paper it’s printed on if it just sits on a shelf. We need to apply the evaluation findings so that we can affirm what might already work but also make changes where needed.

Here are 3 key things we learned from the inREACH experience that could help us more effectively engage young people who are marginalized and better address their needs.

It Works!

Some believe that teenagers – particularly those labelled as “trouble” – don’t want to be involved in community activities or mentoring relationships with adults. The evaluation busts that myth by demonstrating very clearly – that if organizations and communities take the right approach – then many adolescents and young adults, will participate in asset building activities like arts and sports. Many will also seek assistance for challenges they face with things like addictions, gang involvement or finding a job or a home, when they have developed a trusting relationship with an adult who meets them ‘where they’re at.’ The evaluation results also clearly demonstrated that when young people got involved in their communities and received help with life challenges, they experienced many positive benefits and changes. Over 95 % of youth agreed their involvement “helped them move in the direction in life they wanted to go.” For example, youth said:

Some believe that teenagers – particularly those labelled as “trouble” – don’t want to be involved in community activities or mentoring relationships with adults. The evaluation busts that myth by demonstrating very clearly – that if organizations and communities take the right approach – then many adolescents and young adults, will participate in asset building activities like arts and sports. Many will also seek assistance for challenges they face with things like addictions, gang involvement or finding a job or a home, when they have developed a trusting relationship with an adult who meets them ‘where they’re at.’ The evaluation results also clearly demonstrated that when young people got involved in their communities and received help with life challenges, they experienced many positive benefits and changes. Over 95 % of youth agreed their involvement “helped them move in the direction in life they wanted to go.” For example, youth said:

“they taught me to actually think before I acted…just keeping my cool overall and staying relaxed and not being so stressed out.”

“It helped me see the value of myself.”

Learning what it takes – with youth

Sharing our Story describes key elements of the inREACH approach that was so successful. It took

Sharing our Story describes key elements of the inREACH approach that was so successful. It took

- the development of trusting relationships between staff and young people;

- listening to the youth and involving them in decision-making,

- recognizing youths’ strengths, skills, and interests, and

- making programs and services more accessible.

The evaluation report fleshes out some details of HOW to implement these approaches, which is the challenging part.

One illustration follows:

“I don’t think that they have ever had an adult say “what are your dreams?” and “how are you going to achieve those?” and then try to help them… That is my biggest question when I first meet a kid….it gets them thinking…. Then believing in them too and showing them you really care.” (Project staff)

Learning what it takes – the community’s role

inREACH was a collaborative venture of multiple organizations. The evaluation documents how these partnerships enabled organizations to work together more effectively, to work with youth in a different way, to access more services and resources and to “produce systemic change – changes in the way systems and organizations in the community approached the problem of gangs and at-risk youth.” (p 10)

Feedback to Community

It was important to report back to people who shared their thoughts and stories of involvement so I returned to many of the neighbourhood programs. Young people were keen to take the summary booklets and some were excited to see their own photographs featured there. Some youth who had been interviewed wanted the full 140 page version, partly to see if they were quoted there. There was a sense of pride for what they had created and accomplished and some commented on the huge difference the programs made in their lives.

Continuing the Learning

Continuing the Learning

We know that if fewer adolescents and young adults experienced marginalization due to where they live or the challenges they face, then fewer young people would be attracted to gangs as a solution to their problems or to find a sense of belonging. So, it begs the question…. What should the community take forward from this youth gang prevention project?

There’s so much to talk about – outreach, social media, a youth engagement approach, new ways of collaborating across agencies, the role of neighbourhood community centres….

We look forward to working with our community to keep learning, but also move the learning to action. The upcoming event “Engaging marginalized youth” will help us do just that and you can join us on Friday April 11, 2014. Registration is required for the event and you can register here. [UPDATE: this event is now SOLD OUT. You can still register but you will be added to the wait list in case of cancelations.]

There’s always more to learn…

Photo Credits: all photos taken by inREACH youth during PhotoVoice projects. 2012

Posted on: March 25th, 2014 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

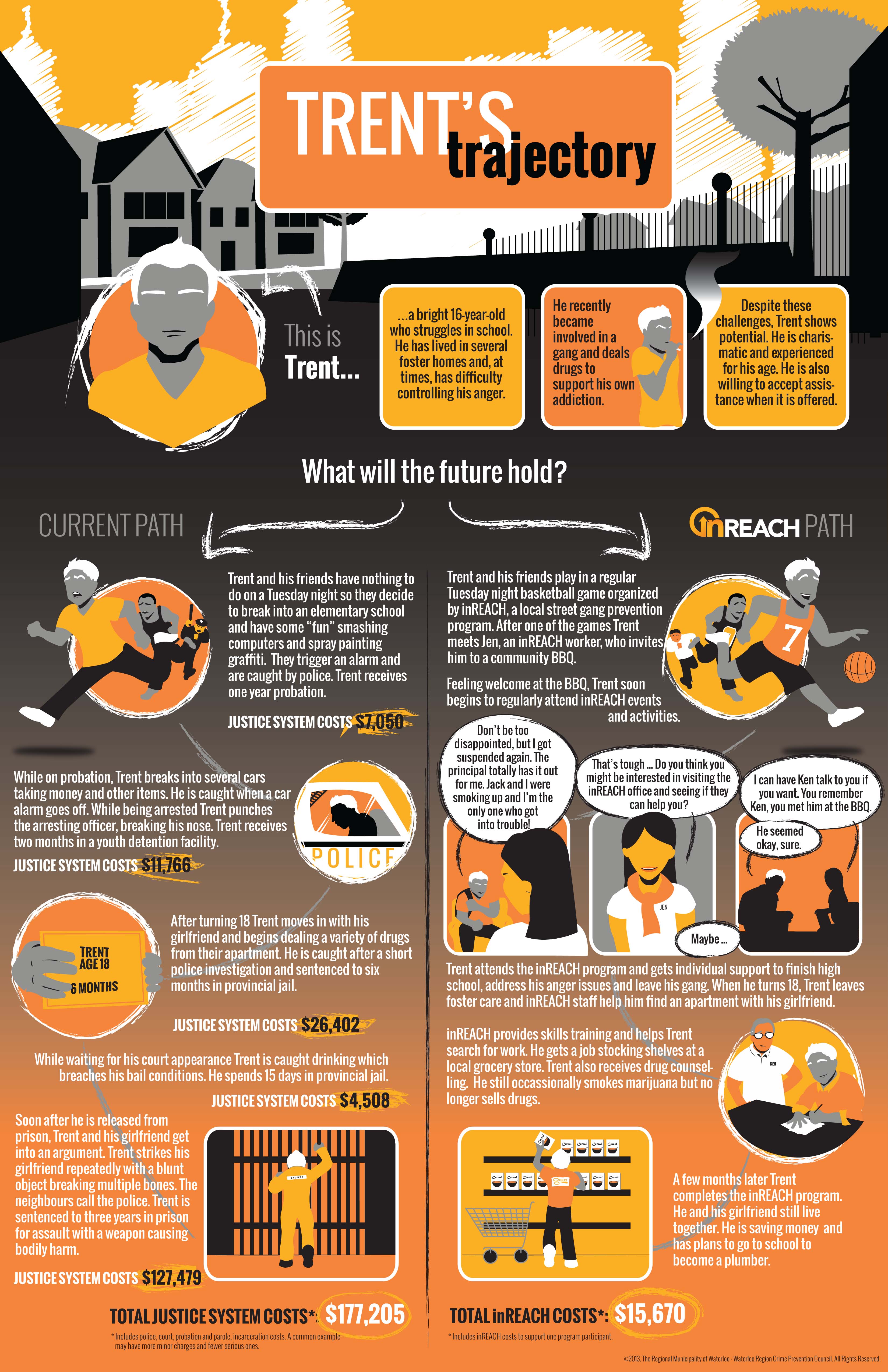

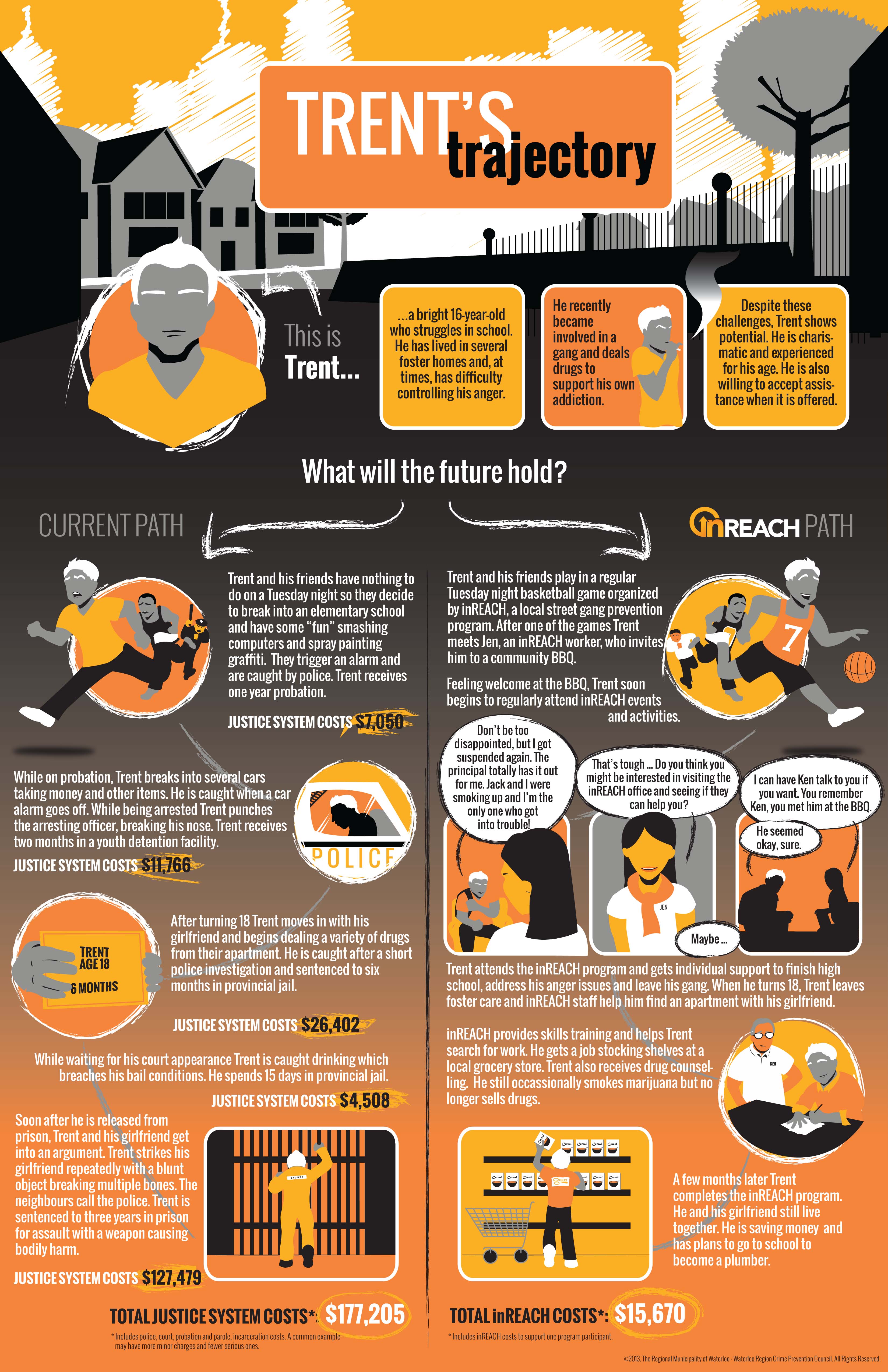

Trent’s Trajectory is fictional account of a sixteen year old teenager as he becomes an adult. The infographic, created by Wade Thompson, begins by discussing the risk and resiliency factors Trent faces. The story then branches into two paths. In the first path, Trent does not receive community supports and his risk factors drive the story culminating in a three year prison sentence. In the second path, Trent receives supports from the inREACH project. His resilience factors grow and Trent successfully transitions into adulthood.

Typical stories from the justice system and the inREACH program build Trent’s fictional story. Due to space constraints the ‘current path’ contains less minor crimes than would be expected from a repeat young offender and a few more serious ones. While this slightly changes the story, the overall justice system costs are realistic. It is important to note, while the story is specifically about the inREACH program similar outcomes can be reached for at risk youth in many other prevention programs.

Does this raise any questions for you? What do we do with this information now that inREACH has ended?

Posted on: March 19th, 2014 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

When a community project ends, such as inREACH, the street gang prevention project in Waterloo Region, it doesn’t really completely end. Sure, the office may be closed, the sign taken down, the telephones disconnected and the staff moved on to other jobs, but things have changed in the lives of youth, individuals and our community.

Even after a project ends, it is our responsibility to capture what worked well and what didn’t so we can continue to change ourselves, organizations, services, systems and ultimately our community to better engage & support marginalized youth in positive action and change.

It takes time to capture what’s been learned, how it applies, who continues the work and how we know it’s making a difference. That’s why we’re hosting:

“Engaging Marginalized Youth: Harnessing Experience from the inREACH Project”

Friday April 11, 2014

9am – 11am

Knox Presbyterian Church, 50 Erb Street West, Waterloo

Please Register if you plan to attend

To make the most of our time together that morning, we have prepared an advance blog series featuring 8 individuals who worked closely with inREACH; project staff, neighbourhoods, evaluators and community leaders. Their thoughts and reflections are sure to stimulate your ideas, – don’t hold back! – post comments and questions to the authors as the blogs are posted so we begin to think and talk about the issues now and can jump right in on April 11th.

Think of this blog series as the pre-game show, starting now.

At the event, it will be up to the community to determine and decide what actions we, the collective WE, can and must take to continue some of the work of engaging marginalized youth in our community.

Please comment, share, tweet, Facebook and reblog this series to help spread the word and share the learning.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at  A big part of these two years was assisting the youth in opening a Youth Art Studio. This studio gave opportunities for at-risk youth to express themselves through the creative arts. It gave the youth a chance to engage in a new and healthy outlet to express their emotions, as well as cope with current and past adversities. I also assisted these youth in running their very first Art Show at a local gallery. Some sold their art, some made the paper; but more importantly I noticed a huge boost of confidence in each of the youth who took part in this.

A big part of these two years was assisting the youth in opening a Youth Art Studio. This studio gave opportunities for at-risk youth to express themselves through the creative arts. It gave the youth a chance to engage in a new and healthy outlet to express their emotions, as well as cope with current and past adversities. I also assisted these youth in running their very first Art Show at a local gallery. Some sold their art, some made the paper; but more importantly I noticed a huge boost of confidence in each of the youth who took part in this.

Author: Paul Field

Author: Paul Field Author: Krista McCann

Author: Krista McCann The most important lessons and understandings learned from inREACH will inspire community action toward a future where all young people feel part of a caring community and have the opportunities and the supports they need and deserve. But, any evaluation isn’t even worth the paper it’s printed on if it just sits on a shelf. We need to apply the evaluation findings so that we can affirm what might already work but also make changes where needed.

The most important lessons and understandings learned from inREACH will inspire community action toward a future where all young people feel part of a caring community and have the opportunities and the supports they need and deserve. But, any evaluation isn’t even worth the paper it’s printed on if it just sits on a shelf. We need to apply the evaluation findings so that we can affirm what might already work but also make changes where needed. Some believe that teenagers – particularly those labelled as “trouble” – don’t want to be involved in community activities or mentoring relationships with adults. The evaluation busts that myth by demonstrating very clearly – that if organizations and communities take the right approach – then many adolescents and young adults, will participate in asset building activities like arts and sports. Many will also seek assistance for challenges they face with things like addictions, gang involvement or finding a job or a home, when they have developed a trusting relationship with an adult who meets them ‘where they’re at.’ The evaluation results also clearly demonstrated that when young people got involved in their communities and received help with life challenges, they experienced many positive benefits and changes. Over 95 % of youth agreed their involvement “helped them move in the direction in life they wanted to go.” For example, youth said:

Some believe that teenagers – particularly those labelled as “trouble” – don’t want to be involved in community activities or mentoring relationships with adults. The evaluation busts that myth by demonstrating very clearly – that if organizations and communities take the right approach – then many adolescents and young adults, will participate in asset building activities like arts and sports. Many will also seek assistance for challenges they face with things like addictions, gang involvement or finding a job or a home, when they have developed a trusting relationship with an adult who meets them ‘where they’re at.’ The evaluation results also clearly demonstrated that when young people got involved in their communities and received help with life challenges, they experienced many positive benefits and changes. Over 95 % of youth agreed their involvement “helped them move in the direction in life they wanted to go.” For example, youth said: Sharing our Story describes key elements of the inREACH approach that was so successful. It took

Sharing our Story describes key elements of the inREACH approach that was so successful. It took Continuing the Learning

Continuing the Learning