Guest Blog

Posted on: October 17th, 2016 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

On November 3, Mike Farwell will join us for Prisons, Justice & Love – an evening with Diane Schoemperlen. And you’re invited too! It’s all part of the Friends of Crime Prevention Turn the Page Book Club, a community reading project to get people thinking and talking about stigma and justice. To get us ready for the community conversation about Diane Schoemperlen’s book This Is Not My Life on November 3, we asked Mike to read the book and share his thoughts.

Reflections by Mike Farwell

There are a variety of compelling reasons to pick up Diane Schoemperlen’s book ‘This Is Not My Life,’ not the least of which would be intrigue at the story of a woman who falls in love with a man who is in jail.

But at the first mention of the word “institutionalized” I was no longer able to focus on the salacious details of this love affair. Instead, I became focused on our prison system and wondered if we needed to redefine its purpose.

Many years ago, I visited Maplehurst Detention Centre, a medium security facility in Milton. The prison is organized into “pods,” with each pod containing 16 cells. You can look into these pods (it really is very much like the zoo or some other attraction designed for our amusement) through a clear yet strong bank of plexi-glass windows and see a common area with concrete tables and some benches along the walls.

The 16 cells are organized eight to a row, with one upper level and another at the ground.

It just so happened that while I was on tour, an inmate was being processed. With a great deal of procedure, and right on cue, the door to the pod was opened and the inmate was ushered inside by a guard.

And then he was greeted like the character Norm from the TV sitcom ‘Cheers.’

His fellow inmates seemed genuinely happy to see him, patting him on the back and calling to him by name. This, to me, is what being “institutionalized” means, and it’s all I could think about after the first appearance of the word in Schoemperlen’s book.

I get the sense that for these men, life “inside” is their normal. When someone returns to their pod, there’s no concern about what crime may have been committed that brought him back into their group. There’s only what passes for the return to normal, a return to a familiar way of life.

Schoemperlen’s love interest, Shane, was institutionalized and had little chance at life outside prison after spending decades within the system. This was immediately evident in the descriptions of the prisons themselves, the rules and procedures within the prisons, the elimination of programs aimed at teaching skills and offering meaningful daily work to inmates, and the complicated parole system on the outside, with its complete lack of understanding of what trying to adapt to an entirely new life is like.

Given the benefit of an objective viewpoint and some experience with our prison system, it quickly became obvious that the romantic relationship in Schoemperlen’s story would fail. Shane stood no better chance of caring for himself than he did nurturing a meaningful, caring relationship with another person.

And if we consider Schoemperlen’s book from this perspective, we’re forced to ask ourselves what the point is of our prison system? Is the system in place to be punitive or is it meant to be transformative? Is there room in our system that would allow for greater chances of rehabilitation and fewer instances of recidivism?

Mike Farwell is co-host of Campbell and Farwell in the Morning on Country 106.7, and the play-by-play voice of the Kitchener Rangers on 570 News. He also writes a bi-weekly column for the Kitchener Post. Born and raised in Kitchener, Mike’s broadcasting career had stops in British Columbia, Thunder Bay, and Toronto before he settled back “home” in Waterloo Region more than ten years ago. Mike is an active volunteer, serving on Kitchener’s Safe and Healthy Communities Advisory Committee and as a trustee on the board of Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region. He is also an advocate and fundraiser for Cystic Fibrosis.

Mike Farwell is co-host of Campbell and Farwell in the Morning on Country 106.7, and the play-by-play voice of the Kitchener Rangers on 570 News. He also writes a bi-weekly column for the Kitchener Post. Born and raised in Kitchener, Mike’s broadcasting career had stops in British Columbia, Thunder Bay, and Toronto before he settled back “home” in Waterloo Region more than ten years ago. Mike is an active volunteer, serving on Kitchener’s Safe and Healthy Communities Advisory Committee and as a trustee on the board of Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region. He is also an advocate and fundraiser for Cystic Fibrosis.

This article reflects the writer’s own opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views or official positions of the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council.

Posted on: February 28th, 2016 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

I attended the Truth & Reconciliation Forum hosted by White Owl Native Ancestry Association (WONAA), to learn about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) recommendations.

There was a wealth of pre-session information shared each week prior to the event, allowing participants to understand more about the history and issues. I must admit, most of this was news to me, which is embarrassing. How did I not learn about this in school? It was a tough session hearing the horrific stories and pain we created for what? To now try and rectify, well, it feels almost impossible. But, this gave me more assurance that I made the right decision to participate in this educational opportunity.

The forum started with a traditional opening of smudging, drumming and singing, in a very connected manner. There were amazing guest speakers, all sharing their unique experiences, touching on one or more of the 94 TRC recommendations.

These recommendations were posted on sheets around the room grouped by category including Child Welfare, Education, Language & Culture, Health, Justice, Reconciliation & Equality, Youth Programs, Missing children & burial Information, Commemoration, Media & Reconciliation, Sports, Business and Newcomers. We were asked to write our email address onto as many of these that we would be interested in further action; so many possibilities to learn more.

The forum closed in a similar manner, respectful of aboriginal traditional practise.

10 Things I Learned about Truth & Reconciliation (What stuck in my mind)

- Change starts with me first.

- I can’t un-know what I now know.

- Knowing never stops; there are layers of learning.

- Healing takes time, at least 175 years (7 Generations principle).

- History is knowledge – it is important to understand in order to do reconciliation.

- The sharing circle approach (connection) is powerful in dealing with reconciliation.

- Reconciliation is personal, bringing one’s spirit to a place of peace.

- Reconciliation is planting the seed for relationship change.

- Conciliation is where we start to create something new, a 3rd space for all.

- There are 10,000-12,000 Aboriginals (First Nation, Inuit and Métis peoples) in Waterloo Region.

For more information, resources and progress, visit the WONAA site of Truth and Reconciliation – A Call to Action.

Community resources are available, “know before you need us”. White Owl Native Ancestry Association Community Resources.

I am grateful for having had the opportunity to participate in this powerful and informative forum. I will use this new understanding in positive ways, helping others to learn and understand too.

~Maureen Trask

Posted on: March 25th, 2015 by Smart on Crime

Never have I seen such a beautiful collection of voices, all unique, and yet all singing the same tune. The Everyday: Freedom from Gendered Violence Symposium put on by the Social Innovation Research Group, and brilliantly detailed by Jay Harrison here, was a phenomenal representation of the intersection of research, arts, and community work. While the Symposium had a particular focus on the university experience, its messages are equally applicable in our neighbourhoods and communities as we think about crime prevention and smart approaches to the gendered violence that occurs in those spaces.

I don’t think I could ever do justice to the amazing topics that were discussed – responding to disclosure, the particular experiences of gendered violence faced by racialized and LGBTQ students, engaging men in prevention, and more. So, I thought the best way was to provide some insight from the speakers themselves:

“What does it mean to be safe?” –Dr. Jenn Root

I sat and thought, ‘good question!’ How can we talk about safety without first talking about what that means? Discussions of violence and crime prevention should always start at the roots.

“Public space is not equal for everyone.” –Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

This rang true for me. How many times have I called a friend or family member to pick me up because I didn’t want to walk alone?

“Did that really just happen?” –Dr. Michael Woodford

Dr. Woodford was speaking about the slurs and comments made to LGBTQ students. But for me, I was struck by the thought of how often we doubt ourselves, as well as our friends and our families when they tell us about something seemingly “minor” is said to them: ‘Oh come on, it’s not so bad…’

“Street Harassment is abuse.” –Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

Tatyana amazed me with this beautiful comparison of street harassment to domestic violence: if a man was yelling derogatory names at his wife, we would call it abuse. When women have cat-calls yelled at them from across the street, however, we tend to brush it off and ignore it.

“The kind of terrorism I want to talk about in this country is domestic violence.” –Judah Oudshoorn

While the media and our governments continue to feed us horrible stories of the atrocities occurring under the umbrella of terrorism, sometimes we forget about the atrocities happening much closer to home – maybe in our homes, maybe in our neighbour’s home.

“Sexual violence is a strategy of war – it is not just against the women, but also the community – it is an attempt to demoralize the community.” –Dr. Eliana Suarez

At the Crime Prevention Council, we often talk about the role of community as a building block for crime prevention. If sexual violence is designed to demoralize a community, then we, as that community, must take a leading role in preventing it.

“Either you’re violent, silent, or creating meaningful change. And if you’re silent, you’re violent.” –Judah Oudshoorn

What a powerful statement. I know which role I choose to play.

“Women are not just resilient, they are resistant – they attempt to change their circumstance.” –Dr. Eliana Suarez

“Maybe there is more than one way to be a man.” –Stephen Soucie

I felt these two quotes belonged together. Discussions around gendered violence often leave me feeling sad and hopeless. But these two spoke of hope, optimism, and change for both men and women.

“It is easier to build stronger children than to fix broken men.” –Stephen Soucie

Again, I felt another ray of hope. Through my research at the Crime Prevention Council, I have learned that early interventions have astonishing success in reducing rates of crime. This is where I think we should be investing our time, energy, and dollars.

“Compliance is important, but compassion is more important.” –David McMurray

An important reminder to wrap things up: while being “tough on crime” continues to get lots of media attention, we would be wise to look at the evidence base and the fact that the majority of “tough on crime” approaches do nothing to reduce crime. Early intervention, prevention that is proven to work, and renewed focus on humane approaches to rehabilitation and reintegration, would go much further toward reducing incidents of crime and victimization.

There were a myriad of other speakers who had insightful comments, but unfortunately, I am only able to present a small portion here. The passion in the room from each and every speaker was evident – from the researchers to the artists to the community workers. They all shared with us their struggles, and yet I came out the other side feeling hopeful and fulfilled. If they can commit themselves to this struggle, they must feel that it is important and that change can be made. As I move forward in working on my Master of Social Work thesis next year, which touches on this topic, I feel like maybe I can contribute a small portion to this struggle. Maybe, someday, we could live in a world where everyday, we were free from gendered violence.

“The struggle is real… the struggle continues” –Janice Lee

How are YOU contributing to the struggle?

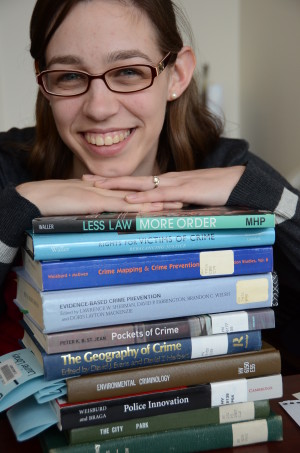

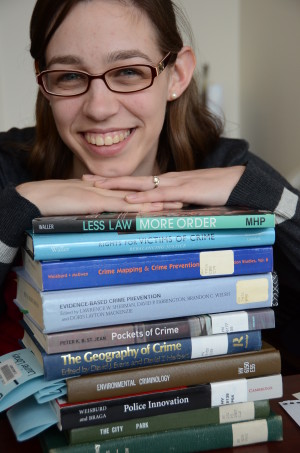

Eleanor McGrath

Author: Eleanor is a Master of Social Work student at Wilfrid Laurier University. She is completing her first placement at the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council, working on a narrative literature review of how crime mapping can be used to implement community-based prevention initiatives. Her favourite hobbies are laughing, rock climbing, and travelling.

Posted on: February 25th, 2015 by Smart on Crime

That’s the response I usually get from friends and family when I tell them that I’ve spent the past two years coordinating a project to address gendered violence against university students. I generally concur with the exasperation, but am quick to point out that it seems unfair to expect to see less gendered violence on campus when relatively little has changed in how we address it on university campuses and in the surrounding communities in which university students live, work and play.

JOIN OUR 2-day Symposium

March 11th & 12th

Engage with campus and community participants on issues related to gendered violence against students in our community.

|

The Change Project, a university-community collaboration funded by Status of Women Canada and led by the Sexual Assault Support Centre of Waterloo Region has taken a long view approach to working toward safer campuses in our region. Over the past 2 years we have talked to over 650 students, staff, faculty and community stakeholders at Wilfrid Laurier University and the University of Waterloo as part of 2 separate needs assessments. The goal of this work has been to understand what our institutions of higher learning are doing well in terms of addressing gendered violence – both in its prevention and response – and what still needs to be done. Ultimately, our aim was to end gendered violence on campus through transforming the institutional and cultural climate of the universities and communities.

Both universities have remarkable capacity to address gendered violence and we have been inspired by the growing attention they have paid the issue over the course of the project. They are also aware of some of the gaps that need to be filled and have begun to demonstrate their capacity to do so in earnest.

What we have learned is that gendered violence – including sexual assault, sexual harassment, intimate partner violence, stalking, biphobia, transphobia and homophobia – is ubiquitous; that is, it happens wherever students are. For students in Waterloo Region that means they are encountering violence in their classrooms and residence buildings as well as in our community: our restaurants and bars, parks, buses, and neighbourhoods. In fact, previous research suggests that most incidents of sexual violence that students experience happen off-campus, outside of the geographic boundaries of the university. And students experience campus life socially, the social boundaries of which can extend quite deeply into our community.

I think this points to a need to look at gendered violence against students as a whole community concern. The efforts of our campuses to prevent gendered violence and support survivors will inevitably fall short if we do not start with a definition of the problem that takes the entire community as its focus and potential site of intervention. How we frame the problem will inform what happens next, who acts and how, and who is held accountable for ensuring student, and by extension community, safety. By broadening our frame of reference we also create an opportunity to draw connections between the gendered violence that is experienced by students with the violence experienced by other members of our community. I believe we can open new doors of possibility for developing truly innovative solutions to an age-old problem by connecting the capacity and knowledge that resides in the university with that of the community.

Are you interested in this topic? The Social Innovation Research Group invites you to join us for a 2-day symposium, Everyday: Freedom from Gendered Violence, March 11th and 12th to engage with campus and community participants on issues related to gendered violence against students in our community. Visit the SIRG website for more information about The Change Project.

Jay Harrison

Author: Jay Harrison is the coordinator for The Change Project at the Social Innovation Research Group. She has been working on issues related to gendered violence against students in Waterloo Region since 2005 when she was an undergraduate student at Wilfrid Laurier University. Jay works with social sector organizations in Waterloo Region and beyond to support their social change efforts through research and evaluation.

Posted on: June 19th, 2014 by Smart on Crime

Prior to my Master of Social Work student placement at the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council (WRCPC) in January of 2014 I had very little, if any, knowledge of the concept of ‘the root causes of crime’. I knew quite a bit about human development, that we are all products of our past experiences, and it was pretty clear that crime is likewise a result of countless influences; it is so much more than ‘bad people’ doing ‘bad things’. What we do and how we decide to act is dictated by all of the tiny events that make up our lives be they happy or sad, wonderful or traumatic, important or seemingly insignificant. The WRCPC addresses these root causes, this infinite web of experiences and events, to help prevent crime before it occurs.

So it sounds pretty simple right? Address the causes before they lead to trouble, is it really that revolutionary? After spending the past six months with this team I can say with conviction that yes, yes it is! There are so few organizations that dedicate their time and effort solely to the prevention of crime and the study of root causes of criminal activity. If you don’t believe me try to search ‘crime prevention’ or ‘root causes of crime’ in any major search engine and not find something about the WRCPC on the first page. Working with this organization has opened my eyes and, to borrow their phrase, I have a better understanding of how to be ‘smart on crime’. Now it is far easier for me to consider the whole picture rather than simply looking at the end result. Because crime is so complex and intricate, it requires equal complexity and intricacy in order to effectively address it.

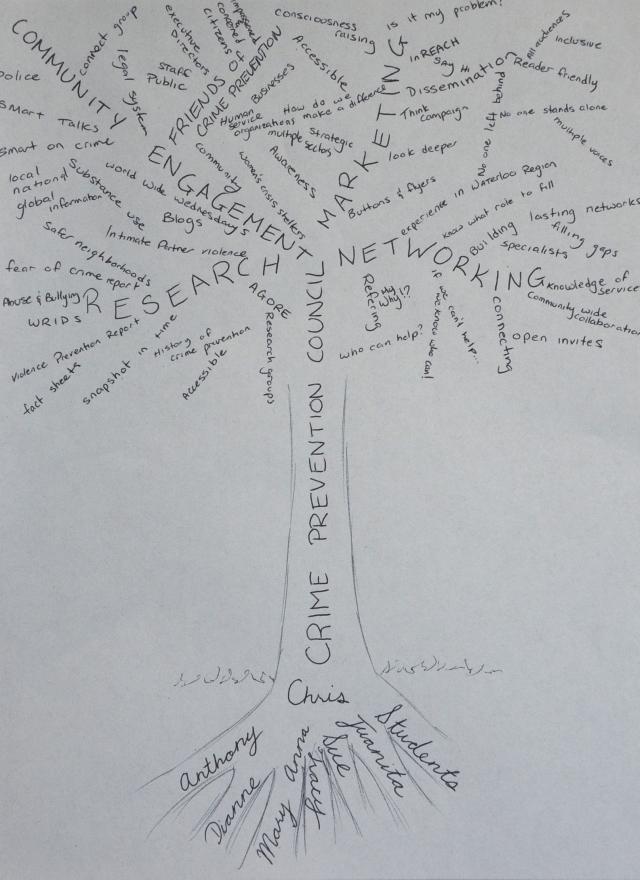

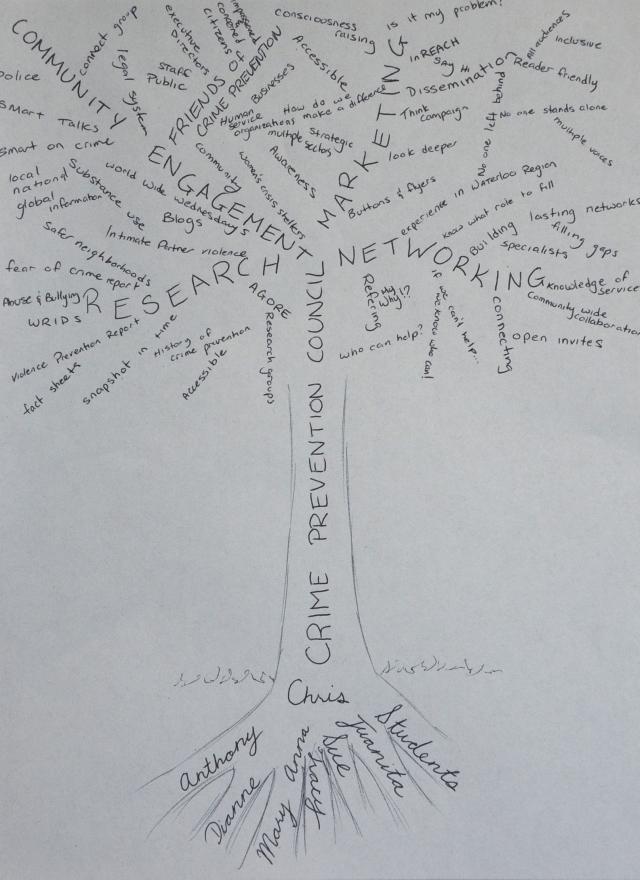

If you will, I would like to share with you my understanding of what the WRCPC really is. Rather than explaining the organizational chart of the WRCPC, which, I am by no means an expert, this is a map of my experiences with the WRCPC. Becausethe majority of the work that the WRCPC does involves providing support, information, and networking opportunities for other human service organizations in the Region, they rarely get the chance to advertise the fantastic work that they do.

The following image is an embodiment of my experiences at the WRCPC. These are the things that I directly witnessed or had a role in completing during my stay and I am sure that I didn’t get it all.

Ryan’s Mind Map to illustrate how he understands crime prevention through social development.

The six staff members are the very foundation of the council, providing the nourishment and support that is needed to complete this vast array of work. Each member plays a significant role and sustains an entire branch of ‘crime prevention’. Christiane Sadeler is the bridge between the staff and the council itself (a body of impassioned community members representing the human services sectors throughout the Region). With this sturdy foundation of staff and council members all of the tremendous work is completed. From academic research to community engagement the WRCPC addresses ‘crime prevention’ from all angles.

It has been such a pleasure to work within this jumbled group. I have learned so much and had the pleasure of working with such meaningful and impactful projects. If you have never had the opportunity to work with crime prevention or just want to know more about what it means do what I did; become a Friend of Crime Prevention. Let’s attend a meeting and have a real discussion about the ways we can make our Region stronger, healthier, and happier. There is always more that can be done and my journey is nowhere near complete.

Author: Ryan Maharaj, MSW Student with WRCPC. Ryan recently moved to Waterloo in pursuit of his Masters in Social Work at Wilfird Laurier University. Placed at the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council, he has been given the opportunity to explore the role of male allies in the movement against sexual and intimate partner violence. He firmly believes that with respect, support, compassion, and education we can prevent the occurrences of sexual violence in the next generation.

Posted on: May 14th, 2014 by Smart on Crime

The conclusion of the InREACH project has been the topic of many well-intended discussions at all levels of our community but we haven’t yet moved to the point of integrating the lessons learned to ongoing or upcoming projects.

On Friday April 11th, the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council hosted “Engaging Marginalized Youth: Harnessing Experience from the InREACH Project” to provide a space for a diverse group of community members – individuals, agencies and neighbourhoods that were involved in the InREACH project – to begin moving from idea to action. Our community learned some very rich and important ‘lessons’ from the inREACH project and the gathering was intended to help the community determine “where do we go from here”. A number of promising ideas were brought to the table, but when all the focus is placed on the next steps, we have a habit of overlooking the negative and possibly dismissing the barriers that inhibit successful implementation.

On Friday April 11th, the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council hosted “Engaging Marginalized Youth: Harnessing Experience from the InREACH Project” to provide a space for a diverse group of community members – individuals, agencies and neighbourhoods that were involved in the InREACH project – to begin moving from idea to action. Our community learned some very rich and important ‘lessons’ from the inREACH project and the gathering was intended to help the community determine “where do we go from here”. A number of promising ideas were brought to the table, but when all the focus is placed on the next steps, we have a habit of overlooking the negative and possibly dismissing the barriers that inhibit successful implementation.

It’s easy to assume that we should apply what we’ve learned from the inREACH project to better support marginalized youth in our community. But have you every stopped to wonder, what happens if we ignore what we’ve learned? What if we shed the rose-coloured glasses and donned the shades of pessimism to see the barriers that stand in our way? What if we tried to see the glass half empty? How can we make a problem like street gangs in Waterloo Region, worse?

Well, let’s see…

- Never discuss inREACH again

- If you absolutely have to discuss inREACH, hold meetings at inaccessible locations when only few people can attend, and only invite individuals who have the power to tie up discussions with bureaucratic process

- Do NOT, under any circumstances, collaborate or foster relationships with other youth serving organizations because it just makes things messy

- Scrap the evaluation and stick it on a shelf. Treat it like it is only the opinion of the evaluator anyway and discredit it

- Speak FOR the youth; adults and service providers know best. Youth are just too young and don’t know what they want

- If anyone asks you about inREACH, only talk about the numbers – how many youth participated, how many completed, etc. Don’t tell the personal stories of change

- Cut funding for youth programs and foster competition over limited remaining resources…. Better yet, just close the services

- Ensure that the remaining youth services only exist in silos and it is really difficult for youth to access them

- Never convene collaborative opportunities for our community to talk about improving our services

- Burn the rest of the inREACH posters and brochures so the program is effectively erased from our collective memory

- Don’t recognize the contributions of all youth in our community and only hand out awards to those that excel at everything

- Use only images that stigmatize youth

- Keeping focusing on the closure of inREACH as a sign that we can do nothing more for youth

Are you getting the picture? Are you thoroughly depressed by the very thought of these ideas?

I’ve used a technique here called ‘reverse brainstorming’ (with some dramatic effect), to emphasize how ridiculous it would be if we ignored what we’ve learned from inREACH and along with it, the potential for positive change. But the important thing here is that it’s not too far fetched if we really do nothing with the gift of what we’ve learned through the inREACH project. The reality is, our region is a growing community and is very close to larger urban centres. We need to keep a focus on prevention approaches so that street gangs do not become a larger problem in our community.

In a reverse brainstorming exercise, those involved would take each spine shivering negative option and flip it to the positive. That is essentially what happened at the “Engaging Marginalized Youth” event but what to do with it? How do we bring all of these lofty suggestions and grand themes together to collaboratively apply the lessons of InREACH? What can we base our practice on?

While the community is working to shape the next phase of work work with marginalized youth, I offer this resource as food for thought. WRCPC has found the work of Tom Wolff, community psychologist, to be inspiring, grounding, and effective in establishing collaborative practice. He presents six principles of collaboration (Wolff, 2010):

- Encourage true collaboration as the form of exchange

- Engage the full diversity of the community, especially those most directly affected

- Practice democracy and promote active citizenship and empowerment

- Employ an ecological approach that builds on community strengths

- Take action by addressing issues of social change and power on the basis of a common vision

- Engage spirituality as your compass for social change

With these six principles in mind, how can we revisit the reverse brainstorming activity above and critically challenge ourselves? Are we using these principles above in our process of applying and disseminating the lessons of InREACH? We can develop our practice to include marginalized youth. inREACH showed us that. We would love to hear your suggestions and thoughts for next steps either through comments below or during future meetings.

If you’re interested in reading more about the “Engaging Marginalized Youth” event, a summary of the event discussion & next steps is available. WRCPC will do its part in continuing the discussion and they are looking to the community to take further leadership. For more information please contact the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council office, by email or telephone, 519.883.2306.

Author: Ryan Maharaj, MSW Student with WRCPC. Ryan recently moved to Waterloo in pursuit of his Masters in Social Work at Laurier University. Placed at the Crime Prevention Council, he has been given the opportunity to explore the role of male allies in the movement against sexual and intimate partner violence. He firmly believes that with respect, support, compassion, and education we can prevent the occurrences of sexual violence in the next generation.

Posted on: April 17th, 2014 by Smart on Crime

We all agree that both the direct and indirect victims of crime deserve society’s help and support. Victims want services to help them come to terms with their trauma, loss, and grief so they can move on. Government supported services, compensation for their injuries, and measures to prevent both the occurrence and reoccurrence of crime are important to victims of illegal action. Recently, the Victims Bill of Rights has proposed to provide this support not by establishing government programs for victims’ assistance but instead by giving victims legal rights and a role at the heart of the justice system. But this role for victims represents a departure from the principles of criminal justice embedded in our legal tradition and protected by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Progress in the development of criminal law was marked by an evolution away from private disputes between victims and alleged wrongdoers and toward the administration of justice by the state. As mentioned in October 27, 2013 opinion piece in the Star:

“one of the greatest innovations of the criminal justice system was the realization that the wrongful injuries people inflict are primarily offences against the public moral order represented by the Queen, not just particular harms to individuals in a given situation.”

While individuals could sue in civil cases to recover for losses resulting from wrongdoing, it was the state that ensured that punishments for wrongdoing responded to criminal harm as an injury to the values of a stable, secure society. In this role, the duty of the state was to punish the criminal harm to the victim while still respecting the basic humanity of the criminal. This second branch of the state’s duty secured the rights to fair trial and appropriate punishment on conviction for the accused, which are the hallmark of the just society. The era of the blood feud and the personal vendetta was over.

The extent to which the present Victims Bill’s ‘rights’ will in fact put victims at the heart of the criminal justice system may be illusory. Bill C-32 is clear that the only parties in the criminal justice system will continue to be the accused and the Queen. The Bill also provides that the rights of victims will be applied in a reasonable manner so as not to disrupt the “proper administration of justice” by causing delay or interfering with the discretion of the criminal justice system decision makers. Victims are expressly not made parties, interveners, or even observers in any criminal justice proceedings. No right to seek a judicial remedy, no claim for damages, and no appeal arises if victims’ rights are infringed. Expectations by victims about their entitlements from the justice and corrections system may well exceed what already over-burdened justice and correction officials are able to provide and victims may well feel disappointed by their newly acquired rights. The only remedy provided in the Bill for that disappointment is the capacity to file a complaint. In view of all these limitations, victims may well come to question whether they received a Bill of Rights or a Bill of Goods.

Definition of Victim

‘Victim’ is defined broadly in the Bill as an “individual who has suffered physical or emotional harm, property damage or economic loss as a result of the commission or alleged commission of an offence”. The offender is expressly excluded but his or her family members who may have incurred harm or damage as a result of the crime are not. If the victim is deceased or incapacitated, the Bill specifies the next of kin or care provider who may exercise the victim’s rights. While the definition of victims refers to ‘individuals’, ‘communities’ are also authorized to make victim impact statements. It is unclear what collection of interests will constitute a ‘community’ and whether community victim impact statements will be considered at all stages of the criminal justice process or just at sentencing.

Rights for Victims

Bill C-32 includes four categories of rights for victims relating to information, protection, participation, and restitution. Generally, providing information about the criminal justice and corrections system and ensuring adequate protection for victims in the criminal justice system is desirable as long as they do not infringe the accused’s ability to make full answer and defense or privacy rights. Since it is the proposed rights to participation and to restitution that pose the most significant challenges to maintaining a fair and effective justice and corrections system, we will concentrate on those.

The victim’s participation rights include the right to convey and have considered his or her views about decisions to be made relating to the investigation, prosecution, and adjudication of the alleged offence and also regarding the corrections and conditional release process. As written, this appears to include the right to provide victim impact statements at each stage which will have to be taken into account.

Unavoidably, these new procedures will cause delays. Despite falling crime rates, the criminal justice system is already overburdened and slow. Long waiting times are not only difficult for those awaiting trial, particularly if they are in detained in remand facilities, but they can violate rights to a speedy trial resulting in an inability to bring an accused to justice. Decision makers in the justice system try to move cases toward resolution as efficiently and fairly as possible. Not only will these decision makers be required to provide information to victims who request it, but they will now be asked to consider the views of the victims about the decisions they are required to make. The decision maker will also be compelled to receive and consider a victim impact statement. While this would take time even if there were only one victim, it would become quickly unmanageable with complex cases involving multiple victims, such as a sophisticated fraud or terrorist incidents. If the stated participation rights of victims lead to costly delays or result in prosecutions having to be dropped due to violations of the Charter right to a speedy trial, is justice served?

Further, victims’ participation rights could conflict with justice officials’ obligations to make impartial decisions when exercising their discretion. For example, a prosecutor may decide whether to proceed to trial with charges based on the public interest and the likelihood of a conviction. A victim impact statement reflecting the trauma experienced by the individual may not be relevant to the determination facing the prosecutor yet he or she would be required to consider it. It is not in the public interest to proceed to trial if there is no chance of a conviction despite a prosecutor’s sympathy for the plight of the victim.

Bill C-32 provides that every victim has the right to have the court consider making a restitution order against the offender and have it enforced as a civil court judgment. The introduction of a right to have monetary order for the victims considered by the court skews both the principles and practices of the criminal justice system. As already discussed, most modern criminal justice systems have evolved away from a system of monetary penalties paid by the criminal or the criminal’s family to the victim. Some countries still have criminal justice systems that include ‘blood money’ — a pay out to victims in satisfaction of a crime. With the proposed Victims Bill of Rights, this outdated practice could be revived in Canada.

While empowering judges to consider ‘restitution’ and even ‘compensation’ is not new, these concepts have been embedded in criminal justice principles. ‘Restitution’ historically had been based on principles of precluding unjust enrichment and benefitting from one’s crime. If a person had stolen property or had sold it, the court could order the property or proceeds of the sale be returned. Over time, the understanding of ‘restitution’ changed to include damages for harm caused to the victims. Orders for restitution or compensation became sentencing options for the judge to consider in assessing the totality of the punishment. In this way, the monetary award is limited by what was a fair and proportionate penalty for the offence. If the offender paid a monetary award, this would discharge some of all of his or her punishment for the crime. Nothing precluded the victim from seeking further damages through a civil court process.

Fines and other punishments involving monetary payment by the offender raise some profound fairness issues in the criminal justice system. Simply put, it is much less onerous for a wealthy person to pay a fine than a poor one. Unless something like a day-fine system is adopted where the fine is based on percentage of income, then this type of sentence violates the equality of punishment essential to a fair criminal justice system. Accordingly, judges have imposed fines, surcharges, restitution and compensation orders with restraint.

While normally judges are required to assure themselves that the offender is capable of paying a fine before imposing it, the Victims Bill of Rights specifically provides that the offender’s financial means or ability to pay does not prevent the court from ordering restitution. Far too many accused are poor, marginalized, battling mental health and addictions and without the lawful means to provide financial compensation to others. If a judge does not impose restitution as part of the sentence, he or she will have to explain why. Judges will likely feel more pressure to make these awards.

The preference for restitution orders also builds an undesirable incentive into the system. With the possibility of having damages covered by just filing a form with the courts, how many more people will identify themselves as victims? How many victims will forego the possibility of an easy recovery of losses to participate in restorative justice practices or other measures that might resolve the issue outside of the formal justice system?

The rights to restitution run the risk of inappropriately importing civil justice concepts into the criminal justice system and undermining core principles of fairness.

Conclusion

The Victims Bill of Rights creates a tension: If the victims’ rights as set out in the Bill are applied, they threaten to undermine principles of criminal justice by placing victims at the heart of the criminal justice. This would erode core principles by slowing down an already overburdened system and skewing it toward a tool for personal vengeance and away from objectivity. If the victims’ rights as set out in the Bill are not applied, then victims will be disappointed and their confidence in the criminal justice system will be further reduced. And there is every reason to believe that the promised rights for victims will fall short of expectations. The Bill provides victims with no standing in the proceedings, a complaint mechanism as a remedy for breached rights, and requires that the Bill be interpreted reasonably so as not to delay proceedings or interfere with the discretion of justice system officials. Rather than create a tension between justice principles and victims’ rights that will be felt by victims and justice and corrections officials at every stage of the system, it would have been better to focus on rights to victims’ services, state-guaranteed compensation, and victim prevention measures. These would have addressed some of the real needs of victims without creating likely harmful pressures and unrealistic expectations of the criminal justice system.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

In 2011, she became the Executive Director of the John Howard Society of Canada, a charity committed to just, effective, and humane responses to crime. Ms. Latimer has a law degree from Queen’s University and a M.Phil. from the University of Cambridge.

She is also a part-time professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa. Her interests are in criminal justice, youth justice, corrections laws, human rights, justice systems programs and policies, and policy and law reform.

Reprinted with permission from the author.

Posted on: April 7th, 2014 by Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council

Before inREACH ended in December 2013, I shared 5 important lessons learned from the inREACH gang prevention project with the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council. While project funding has ended, some parts continue and there is much to be learned about addressing youth gang involvement in our community for the future. Here are some highlights.

1. What are your assumptions and values?

We need to ask ourselves this central question – what are the fundamental assumptions and beliefs we have about the young people we work with? Do we feel people are broken and need to be fixed? Or – do we believe people are full of capacities and if supported correctly, they can realize their potential? I’m not saying people don’t come with their problems, but the question is what are we focused on because that informs how you do the work. It took us a while to get this right. This idea was expressed well by a youth participant:

“It’s…for us, run by us and gonna involve all of us..What do you want to see in your community, and what are your personal talents or anything that is special to you that you want to show everybody else, and maybe those people might like it too right? So- opening new opportunities. It’s not just to keep kids off drugs but for under-privileged kids, kids who may have never had a chance to be part of something like you know…discover their love of art…so it’s giving everybody a chance to actually do…the things they want to do, so that’s why I started coming.”

This is powerful because it’s raising the bar. It’s not just getting youth out of the gang – but getting them into a job or back in school and even realizing some of their hopes and dreams. If you believe that people are full of possibilities – then the work is geared more to helping people realize that potential versus simply preventing them from doing something.

2. Gang Prevention Is:

- addressing underlying issues

- not about getting a kid to take off the bandana

We often heard – “we’ve got this kid, he’s in a gang – fix him.” So often in our case management and system navigation work, it wasn’t about getting this young person to take off his bandana or to stop hustling or whatever, we never approached the work in that fashion. But it was about the underlying issues and working on them. Mostly we were dealing with issues of poverty, untreated trauma, family breakdown, substance abuse, disengagement and lack of opportunities. These are the problems that young people and gang members and people in general are dealing with. We want to demystify that label of gang member that says their needs are different than any other groups. These same issues are the drivers behind the behaviours.

3. Gang prevention is:

- increasing engagement and inclusion

- working at individual and community levels

Young people demonstrated so clearly that they WILL engage. This matters because pro-social relationships and connections are essential for preventing youth from participating in gangs.

Unfortunately, adolescents and young adults are much less involved in community activities than other groups, particularly those experiencing marginalization due to where they live or challenges they face. Researcher Mark Totten says “there is an epidemic of social exclusion in Canada.” inREACH very successfully supported young people’s inclusion and engagement, in community centres, recreation, school, employment, services and more. This is a promising way to build assets and address risk factors in a holistic and non-stigmatizing way. However, it wasn’t just about engaging individual youth. The community was also mobilized and systems needed to make some changes in order to be more inclusive.

4. inReach is an example of an effective hub model

inReach is a comprehensive wraparound hub model demonstrating an effective way to support young people. It was comprehensive because all the right supports, services, staff and organizations were involved. It was a mobile hub which was key for meeting young people where they’re at – whether at the office, Tim Horton’s or their home. Dedicated multi-disciplinary teams brought diverse skills to the work and learned strategies and skills from each other. It was not done at a desk.

5. You Need The Right People On The Bus

You need to have the right people and organizations involved in the project and that was really key to the success of inREACH. People have to be there for the right reasons, share the same vision and be able to check their egos at the door. It can’t just be about what’s good for your own organization. Collaboration requires a thoughtful discussion before you bring people on the team. Everyone involved with inREACH was fully invested and went above and beyond because they were passionate and believed in it.

The community should be proud of all that it has accomplished.

Co-authors: Dianne Heise & Rohan Thompson – Dianne Heise is the Coordinator of Community Development and Research with the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council and worked with the inREACH project while she was a Master of Community Psychology student at Wilrid Laurier University. Dianne also worked on the final evaluation of the inREACH project with Dr. Mark Pancer (WLU).

Rohan Thompson was the Project Manager for the inREACH Street Gang Prevention Project (2010 – 2013). At the end of the project, Rohan returned to his role with the City of Kitchener.

Rohan Thompson (L) and Dianne Heise (R)

Posted on: April 3rd, 2014 by Smart on Crime

Alison Neighbourhood Community Centre is neighbourhood-based organization that works with volunteers to support residents who live in the Alison Neighbourhood in East Galt, Cambridge. We support residents, families, children & youth by offering after school programs, youth drop-in programs, community events, family outreach services, and volunteer opportunities.

As a member of the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council and as community partners of a couple of the InReach project host sites, we were able to hear about some of the wonderful opportunities to which the youth were exposed as a result of InReach that they would not have experienced otherwise.

How InReach Resonated with the Work We Do

- We too, focus on building on strengths and capacities of young people

We have worked with youth who have great dreams and aspirations for the future, but have trouble putting their vision into a workable plan. On the other side of the coin, we have worked with youth who have little to no confidence in their abilities, thus requiring a little more encouragement and a little more trial and error in determining what really gets them motivated and excited.

In our experiences, many youth have difficulty simply picking up a new hobby as a means to divert themselves from more harmful and negative activities. Let’s say a young person decides to try something new: Inspired by an Instagram pic of a friend of a friend’s cousin rock climbing out West, Andrew decides he wants to give it a try. A few initial barriers come to mind: Other than that distant personal connection, he doesn’t know anyone else who rock climbs, he doesn’t know where he would go to rock climb, and has no idea what is needed to get started. How much is it to join? Do you need a membership? What type of equipment is needed? Does that cost more money? The idea is now overwhelming. For a youth who has not had many life experiences nor opportunities, it is likely that these questions wouldn’t even be on their radar. It is much easier to continue along their existing path, wherever it may lead.

In our experience, the recipe for youth engagement is as follows:

- Exposure to a new activity must take place in an accessible space where youth feel safe, where they won’t feel like they are being judged and feel comfortable to try, fail, and then try again

- In order for this to happen, relationships must be built with program staff. And in order for this to happen, staff must be skilled in outreach and community development practices so that they can effectively meet the youth where they are at before they will even walk through your door

- Youth need to be involved in the planning process and have input and control over what happens next

- It takes time, commitment to seeing the initiative through, trial and error, one-to-one support, and constant encouragement to ensure that youth are getting the most out of the program.

Bottom Line: You cannot expect certain youth to simply sign up for an activity, attend regularly, and thrive without support, a trusting relationship and input into the program’s design and execution.

- We have learned to adapt to the growing complexity of the needs and issues of youth

We offer programming for youth under the guise of recreation. When I first started working in the field, I had a very pretty picture in my mind about what the harmonious world of recreation should look like: Mom or Dad would drop off their kid for our program, (on time), sign-in would be completed in an orderly and organized fashion, and we would all participate in an rousing round of basketball. At programs end, the youth would depart safely for the evening and everyone would be so happy. I hope you can smell the sarcasm here, because this picture couldn’t be any further from our reality. On paper, we offer programs such as Teen Night, Basketball, Girls Night, etc. In reality, we offer mentorship, leadership development opportunities, a place to belong and be heard, support and guidance, a respite from family and relationship trauma, something to eat, relief from the stresses of coping with depression and anxiety, an escape from the pain and constant disappointment of poverty, an opportunity to practice speaking English, access to individualized supports such as counselling, emergency food sources, career resources, addictions supports, relationship and grief therapies, and the list goes on and on. Ultimately, by the time we have a chance to check in and talk to everyone who was fortunate enough to even arrive to the program, there often isn’t time to play basketball.

- We need help keeping programs like these going so that we can reach more youth

Just because the InReach project is now “complete” doesn’t mean that there still isn’t more work to do. With as many partners, staff, support agencies and youth impacted by InReach, I hope that the trajectory of this valuable project will not be lost and its lessons forgotten. The truth is, there are thousands of youth living in the Waterloo Region that could really benefit from a community treatment team; a one-stop-shop where youth can access support to face a combination of issues (see above) unique to only them, right in their own neighbourhoods. Effectively addressing these issues takes partnerships, patience, commitment, resources- all things that that the InReach project so successfully exemplified.

Author: Courtney Didier is the Executive Director of Alison Neighbourhood Community Centre in Cambridge. She is very passionate about creating sense of community and inclusion, not only in her neighbourhood, but across the Waterloo Region. Courtney is expecting her first child any day now!

Posted on: April 2nd, 2014 by Smart on Crime

Being an avid hockey fan, I await the joys of the upcoming Stanley Cup playoff run. But with this expect many interviews, with standardized questions with the same responses from each player. The questions never change based on a given answer, and the answers never change from game to game, and year to year for that matter. They are all cliché based interviews. How is this relevant to inREACH?

Having been with inREACH, it became quite evident, that the youth we worked with often experienced clichés in their lives. They were labelled, stereotyped, and their behaviours were often predicted by the adult world around them, yet most of the time no one knew anything about them. Outside of where they lived, or who they hung out with, or the school they went to, or perhaps what they look like, do many even know these youth? The label which is the umbrella they live under is their cliché.

While working with inREACH, the approach we used broke down these barriers, the labels, the assumptions. That is what worked. Did we listen to them? No; we heard them. We can use our own clichés about giving hope, opportunity, a chance, but it only works if we know what to give. That was done by hearing their story. Their story does not have to be a given. It is not just about where they have come from, and what they are going through, it is also about where they want to go. If we hear them, we can help them. inREACH worked because no assumptions were made. Each youth had their own “Stanley Cup” they wanted to lift, but the battle to get there was the unknown. After each session or meeting with a youth, there were no cliché answers or questions. There was the concept of acknowledgement of ability, an identification of assets, and no reason to suggest why that youth could not raise that cup, whatever that cup was from him or her.

There was a time where we were asked to do a presentation on working with high risk youth on behalf of a community agency, and the reason for such information was the staff was stressed due to not feeling successful in working with this population. Initial feedback as to why the training was needed was the youth do not listen; they are always angry, disrespectful etc. Perhaps part of the issue is as adults, we make assumptions of where these youth have come from. This was a huge learning curve I believe many of us have yet to master.

Recently I watched the film “Short Term 12”, about youth in a group home, and a new staff member in the film was asked to say a few words to introduce himself to the group. His response was: “I always wanted to work with under privileged youth”. That comment didn’t go over very well. My first reaction was shock really, as the moment the categorization of ‘under privileged’ was used, any potential trust is already gone (as the youth were not too happy). The scene reminds me so much of what inREACH was about. Youth are…really….just youth. No adjective required. And really, I do think that is what is being missed. That point was driven home while with inREACH.

Often, we as adults rely on labels, as they are easy to work with clichés that fit into a nice little box for the ease of comfort.

In my continued work, I think it is of the upmost importance to truly find out what the youth needs, or wants, and feels. To reflect on what the youths’ words are, shows they have been respected, and valued, and heard. That is the start of their quest for their Stanley Cup.

Moving forward, what is my message? I won’t give any clichés here that you will assume I should be making now. What I will say, is do you know the path I took as a youth to get to where I am right now (working in social services for 14 years)? I will bet most likely not. I was a youth. We all were. That is the cliché I will end off on!

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at John Howard Society with the Youth in Transition Program, a program for Crown Wards. And want to know a fun fact…? I still play my major passion every week…HOCKEY!

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at John Howard Society with the Youth in Transition Program, a program for Crown Wards. And want to know a fun fact…? I still play my major passion every week…HOCKEY!

Mike Farwell is co-host of Campbell and Farwell in the Morning on Country 106.7, and the play-by-play voice of the Kitchener Rangers on 570 News. He also writes a bi-weekly column for the Kitchener Post. Born and raised in Kitchener, Mike’s broadcasting career had stops in British Columbia, Thunder Bay, and Toronto before he settled back “home” in Waterloo Region more than ten years ago. Mike is an active volunteer, serving on Kitchener’s Safe and Healthy Communities Advisory Committee and as a trustee on the board of Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region. He is also an advocate and fundraiser for Cystic Fibrosis.

Mike Farwell is co-host of Campbell and Farwell in the Morning on Country 106.7, and the play-by-play voice of the Kitchener Rangers on 570 News. He also writes a bi-weekly column for the Kitchener Post. Born and raised in Kitchener, Mike’s broadcasting career had stops in British Columbia, Thunder Bay, and Toronto before he settled back “home” in Waterloo Region more than ten years ago. Mike is an active volunteer, serving on Kitchener’s Safe and Healthy Communities Advisory Committee and as a trustee on the board of Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region. He is also an advocate and fundraiser for Cystic Fibrosis.

On Friday April 11th, the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council hosted “Engaging Marginalized Youth: Harnessing Experience from the InREACH Project” to provide a space for a diverse group of community members – individuals, agencies and neighbourhoods that were involved in the InREACH project – to begin moving from idea to action. Our community learned some very

On Friday April 11th, the Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council hosted “Engaging Marginalized Youth: Harnessing Experience from the InREACH Project” to provide a space for a diverse group of community members – individuals, agencies and neighbourhoods that were involved in the InREACH project – to begin moving from idea to action. Our community learned some very  Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

Author: Catherine Latimer spent many years as a legal policy analyst for the federal government, both at the Privy Council Office and later as the Director General of Youth Justice Policy at the Department of Justice.

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at

Author: Karl Garner I was a Case Manager at inREACH a focus on employment for the youth. I am currently working at